You are here: Foswiki>Dmi Web>WinterSchool2020youtube (24 Feb 2020, SalvatoreRomano)Edit Attach

YouTube Tracking Exposed: Investigating polarization via YouTube ’s Recommender Systems

Team Members

Nina Altmaier Davide Beraldo Maria Castaldo Daniel Jurg Salvatore Romano Matteo Renoldi Tatiana Smirnova Natacha Seweryn Luukas VeivoContents

Team Members ContentsSummary of Key Findings

1. Introduction

2. Research Questions

3. Methodology

3.1 Datasets

3.2 Qualitative Analysis

4. Findings

4.1 Video Recommendations

4.2 Channel Recommendations

4.3 Qualitative Analyses of Brexit Recommendations

5. Discussion

6. Reflections/ Limitations

7. Conclusion

7. References

8. Appendix

8.1 Adèle Haenel and pro/against #metoo polarization

8.2 Trexitors

Summary of Key Findings

- There is evidence of progressive polarization of the recommendations around Brexit on YouTube, especially for Leave-inclined users.

- The Leave/Remain content bubbles, constituted respectively by The Sun/The Telegraph and The Guardian/The Mirror YouTube channels rarely converge.

- Mainstream media is recommended with greater regularity compared to natively digital channels.

1. Introduction

Over the last few years, the creation of ‘filter-bubbles’ and the issue of algorithmic radicalization has sparked significant controversy within academia and privacy-focused collectives. In this literature, YouTube especially has come under scrutiny. In 2019, Ribeiro et al. have sought to computationally verify the ‘anecdotal literature’ on the ‘radicalizing power’ of YouTube ’s Recommendation Systems (RSs). They argued that there is indeed empirical evidence to confirm the hypothesis that users navigate along with YouTube Recommendations. Contrary to this research, at the end of 2019, Ledwich and Zaitsev claimed that the hypothesis of YouTube being a platform for algorithmic radicalization to be actually false. Instead, they highlighted how YouTube recommends a more mainstream type content to its users. In other words, blaming the algorithm for creating niche viewing behavior might be incorrect. The aforementioned articles (and scholars) have also become the center of discussions on Twitter. Prominent journalists Zeynep Tufekci and Kevin Roose, as well as scholars, e.g. Becca Lewis and Arvind Narayan, writing on the topic of YouTube ’s algorithm have questioned the validity of the methods used to study RSs (Feuer). The main critique here is methodological, i.e. studies into RSs have relied on YouTube ’s official API, which, arguably, does not give an accurate representation of users’ actual experiences. As Narayan points out: “They [Ledwich and Zaitsev] reached their sweeping conclusion *without logging in*…” (ibid.). Ribeiro et al. already pointed out that their “analysis does not take into account personalization, which could reveal a completely different picture” (10). While some scholars have suggested moving away from RSs (Munger and Phillips), it is still the case that YouTube ’s algorithm accounts for 70 percent of videos watched on the platform (Newton) and, therefore, is worth investigating. This Winter School project seeks to study algorithmic recommendation from a user perspective in an attempt to move towards post-API research. Specifically, empowered by youtube.tracking.exposed’s infrastructure, we have been able to highlight filter bubbles visually and statistically as a by-product of polarization dynamics. Taking Brexit as an emblem for a divisive issue, this project aims to map in which way the algorithm guides users through the enormous supply of Brexit videos and how this algorithmic guiding might polarize users interested in the topic coming from divergent political backgrounds.2. Research Questions

The following have been our two leading research questions:- Do YouTube ’s recommendation systems enhance and potentially incentivise users’ polarization on a specific topic?

- How might users experience Brexit polarization on YouTube?

3. Methodology

The aim of this project was to try to understand the inner logic of YouTube ’s recommender algorithm by taking into account the videos recommended to different research personas. Crucially, we made use of the youtube.tracking.exposed tool which allows us - in contrast to YouTube ’s official API - to retrieve data about users’ personalized experience. This is possible as a result of the passive scraping performed by the browser extension on the videos’ pages. We conducted experiments on two separate topics and refined the methodology after the first experiment. Our initial research was focused on a controversy arising from the French YouTube -sphere concerning the following video “French actress Adèle Haenel accuses filmmaker of 'sexual harassment' when a minor”. This was a video that sparked significant debate in France between feminists and more conservative-leaning groups. We performed four different tests, each time retrieving the recommendations given on the aforementioned video through the youtube.tracking.exposed web extension. For all the tests were started with a clean, cookie-free browser as a baseline setting and the “French (France)” language as a default to reduce the influence of system variables. The following are the four different tests that we performed:- The video was accessed directly via the URL through a simple copy-paste.

- Half of the team accessed the video from a right-leaning website (Appendix 8.1) and the other half from a left-leaning website (Appendix 8.1).

- Half of the group watched five left-leaning videos on the topic (Appendix 8.1). The other half right-leaning videos (Appendix 8.1). Afterward all accessed the initial video through a copy-paste.

- Half of the group watched five left-leaning videos on the topic, while the other half right-leaning videos. Following this, the groups switched videos, watching the videos the other “side” had seen. Afterward all accessed the initial video.

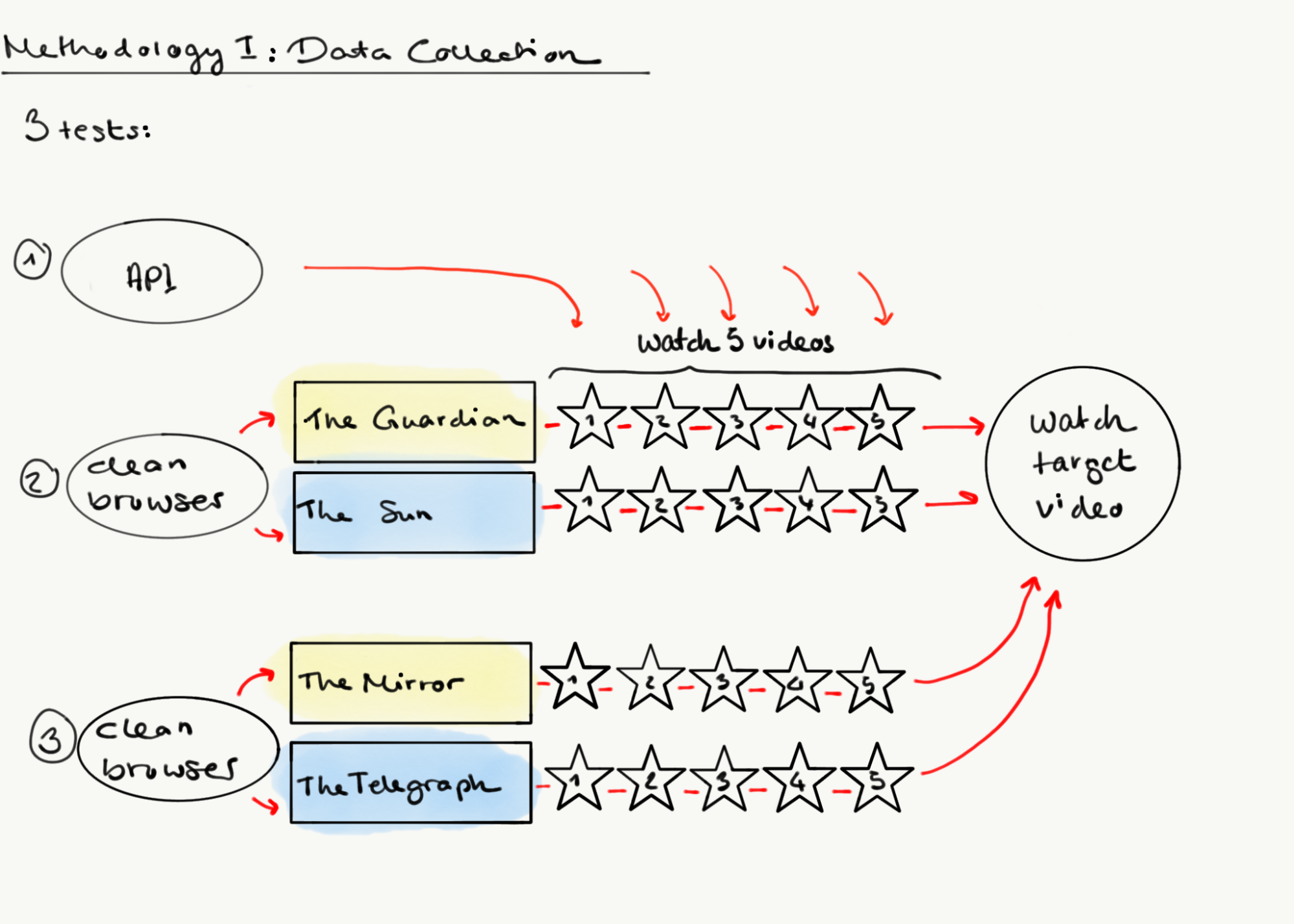

- Half of the group watched five videos from The Guardian. The other half watched five videos from The Sun. Afterward all accessed the ‘neutral’ video.

- Half of the group watched five videos from The Mirror. The other half watched five videos from The Telegraph. Afterward all accessed the ‘neutral’ video.

Figure 1: Methodology for Data Collection

Figure 1: Methodology for Data Collection

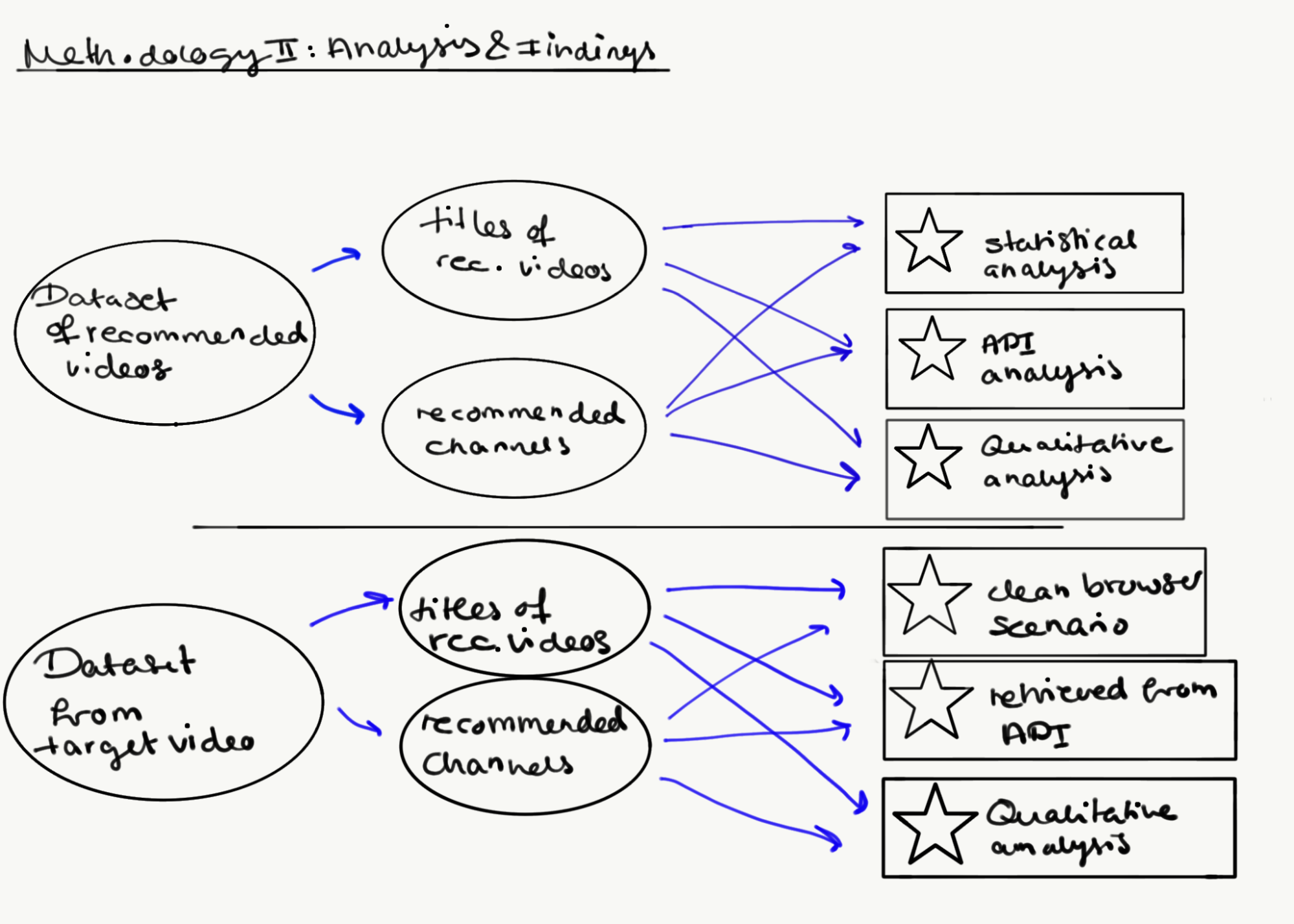

Figure 2: Methodology for analysis of the findings

Figure 2: Methodology for analysis of the findings

3.1 Datasets

The size and shape of our datasets have been defined by the functioning of the youtube.tracking.exposed web extension. This browser add-on is able to save and store the video that is being watched but also the metadata of the first twenty suggested videos that appear on the right side of the screen.3.2 Qualitative Analysis

In order to ascertain what effect the partisan stance of each of the two ‘research personas’ constructed for the experiment had on the nature of the content recommended by Youtube, a subset of our group carried out qualitative research designed to map out the political position of each recommended channel from each of the scenarios listed above. To carry out this task, a list of the recommended channels was retrieved from the datasets, after which their individual position on the issue of the Adele Haenel affair and Brexit was determined through a qualitative analysis of their political leanings. This was determined primarily on the basis of both the channels’ own description of themselves, as well as the subject matter and tone of their video content when the former proved less explicit – a method resolved as best in the interests of the limited time allowed for the research project. For the main experiment concerning polarisation around Brexit, this data also formed the basis of two graphs we created using Tableau. The first was a set of 5 pie graphs conflated into one pane, each showing the absolute number of recommended channels subscribing to one of 4 political positions (Leave, Remain, neutral, or irrelevant) divided according to the type of media they represented (alternative media, government, influencer, mainstream media, other). In addition, to further elucidate the qualitative nature of and possible links between the content bubbles surrounding each of the 4 publications chosen for the experiment, the data we had retrieved was also used to create a word map of the top 10 keywords occurring in the titles of the first 20 recommended videos for each of the main channels.4. Findings

4.1 Video Recommendations

Figure 3: Shared titles within different bubbles

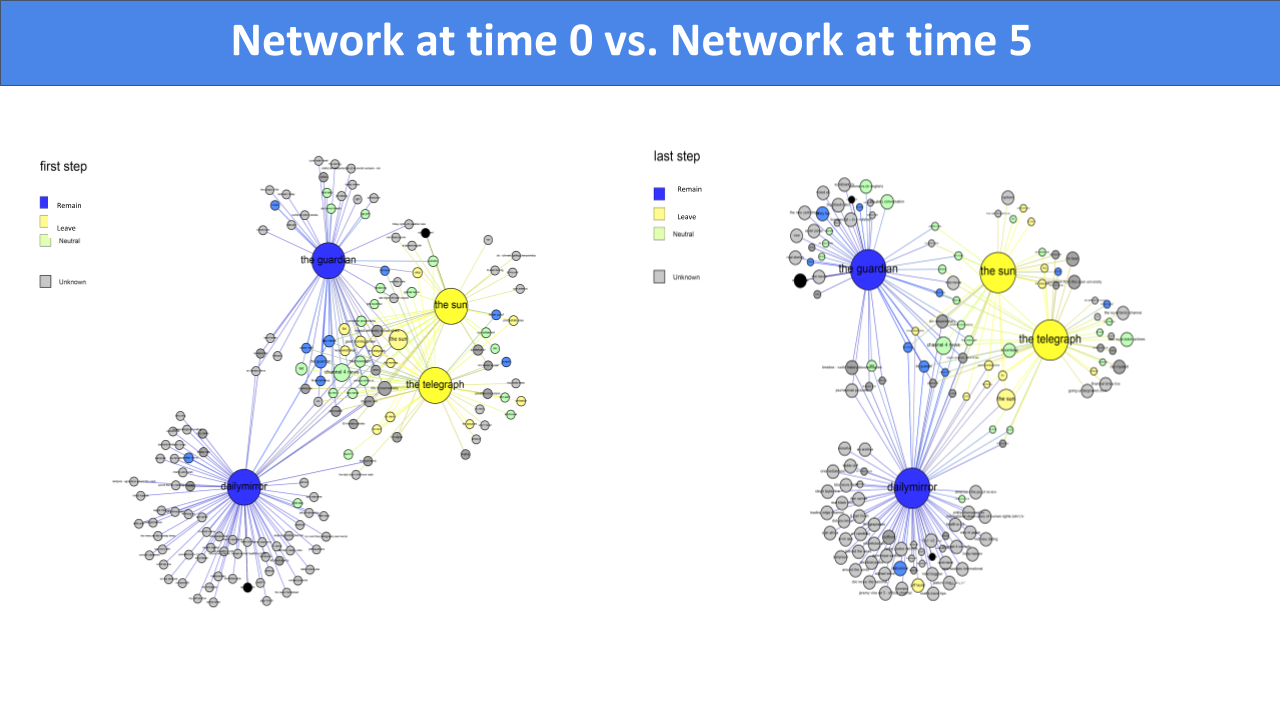

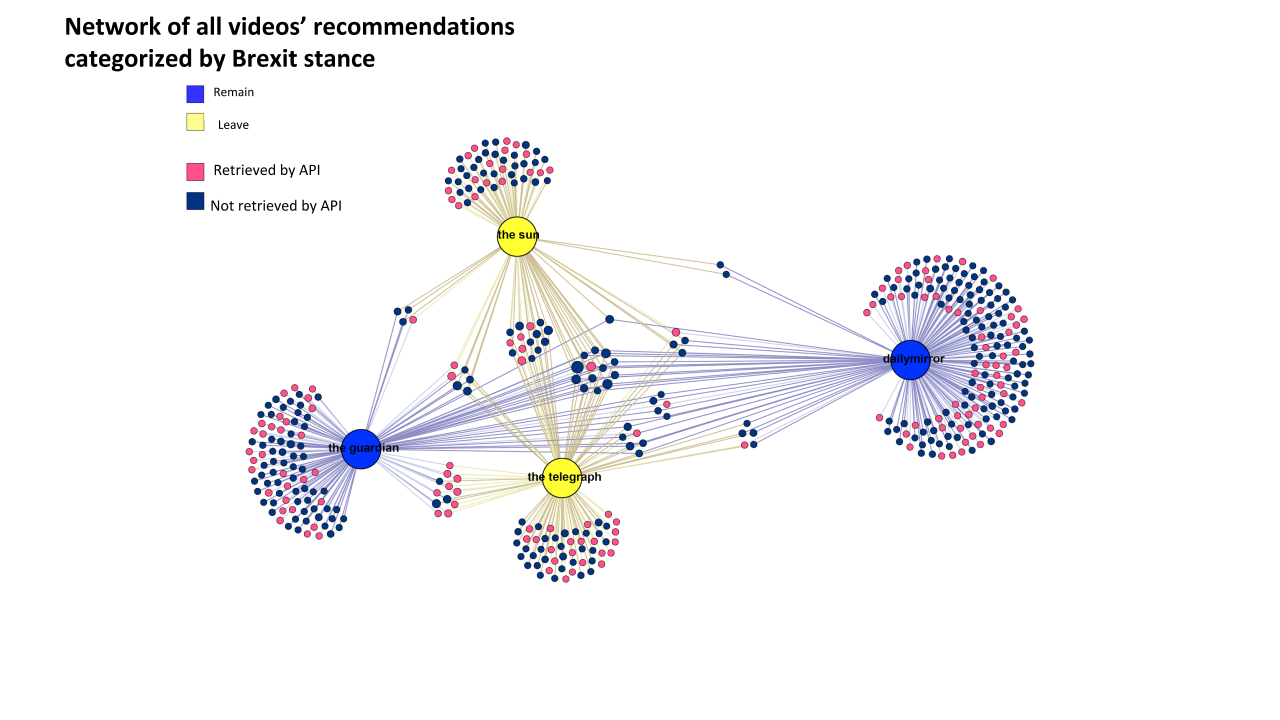

We investigated the number of suggested videos shared by different users. In Figure 3, we aggregated in 4 major nodes the users that have been profilized by watching videos published by the same channel. Smaller nodes represent the video they have been recommended. The graph was generated using only the suggestions received after watching 5 videos coming from the same channel. As we can see, many videos belong to a “bubble”, an evident result of personalization.

Then, we focused on the number of suggested videos shared by Leave users (in yellow in Figure 3), i.e. users trained with videos coming from The Telegraph or The Sun channels, and Remain users (in blue in Figure 3), i.e. users trained with videos coming from The Guardian and The Daily Mirror. We investigated how this quantity changes over time, i.e. as the number of videos used to personalize profiles grows from 1 to 5. The result is a dynamic network graph presented by the following video.

Video 1: Evolution of shared suggested videos within different user groups

As shown by the video (Figure 4), the number of videos suggested to both Remain and Leave users seems to decrease as the personalization goes on. We decided to formally test this result by defining a measure of similarity between clusters as a measure of similarity between the suggestions proposed to Remain and Leave users and to test the availability of statistical evidence of the similarity decrease.

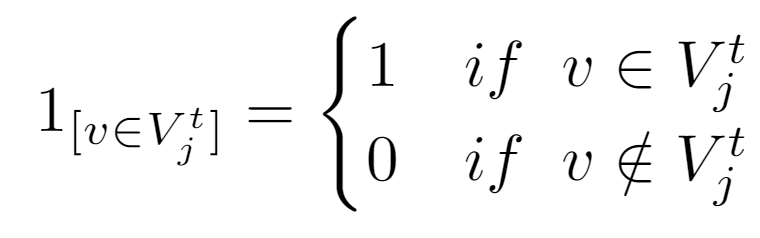

To give a formal definition, let us call

Figure 3: Shared titles within different bubbles

We investigated the number of suggested videos shared by different users. In Figure 3, we aggregated in 4 major nodes the users that have been profilized by watching videos published by the same channel. Smaller nodes represent the video they have been recommended. The graph was generated using only the suggestions received after watching 5 videos coming from the same channel. As we can see, many videos belong to a “bubble”, an evident result of personalization.

Then, we focused on the number of suggested videos shared by Leave users (in yellow in Figure 3), i.e. users trained with videos coming from The Telegraph or The Sun channels, and Remain users (in blue in Figure 3), i.e. users trained with videos coming from The Guardian and The Daily Mirror. We investigated how this quantity changes over time, i.e. as the number of videos used to personalize profiles grows from 1 to 5. The result is a dynamic network graph presented by the following video.

Video 1: Evolution of shared suggested videos within different user groups

As shown by the video (Figure 4), the number of videos suggested to both Remain and Leave users seems to decrease as the personalization goes on. We decided to formally test this result by defining a measure of similarity between clusters as a measure of similarity between the suggestions proposed to Remain and Leave users and to test the availability of statistical evidence of the similarity decrease.

To give a formal definition, let us call  Once defined this measure and evaluated the two samples at time

Once defined this measure and evaluated the two samples at time  Figure 5: R code of t test execution

Such a low p-value, noticeable in Figure 5, stands for statistical evidence of the difference within the two means to be significant. Therefore, we can state that the similarity of suggestions between the Remain and Leave users decreases over time and that it is already significant after a personalization built on watching just five videos.

Figure 5: R code of t test execution

Such a low p-value, noticeable in Figure 5, stands for statistical evidence of the difference within the two means to be significant. Therefore, we can state that the similarity of suggestions between the Remain and Leave users decreases over time and that it is already significant after a personalization built on watching just five videos.

4.2 Channel Recommendations

4.3 Qualitative Analyses of Brexit Recommendations

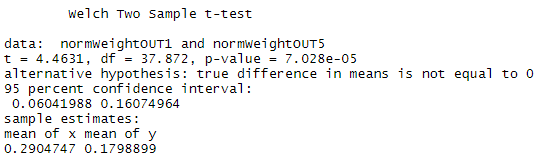

Two kinds of qualitative analyses have been performed: (1) a categorization of the recommended channels and (2) a word association of the recommended video titles. First, in order to see what type of channels were recommended and how they were positioned on Brexit we performed a close-reading of the channels to get a sense of their content and possible stand. Figure 7: Categorization of Recommended Channels

Figure 7 highlights that, contrary to earlier research on YouTube, where audiences are argued to be led to more fringe or niche content, we found that, when departing from mainstream outlets, users would be recommended more mainstream channels albeit mostly the same mainstream channels. There were some influencers, but these were not specifically ‘alternative political influencers’ that exploit the political potential of the platform to circumvent mainstream narrative reported by traditional news outlets, as has been argued by Rebecca Lewis. Moreover, ‘alternative media’ in our analysis refers to natively digital content (Rogers 5), i.e. outlets that were ‘born on the web’ rather than, as the outlets with which we began, migrated to the web. While Figure 7 does not distinguish unique channels, it does show that in general pro-Brexit positioning allows for more recommendations on YouTube. Finally, we also found some that we re ‘irrelevant’, i.e. channels without distinct political stance or content.

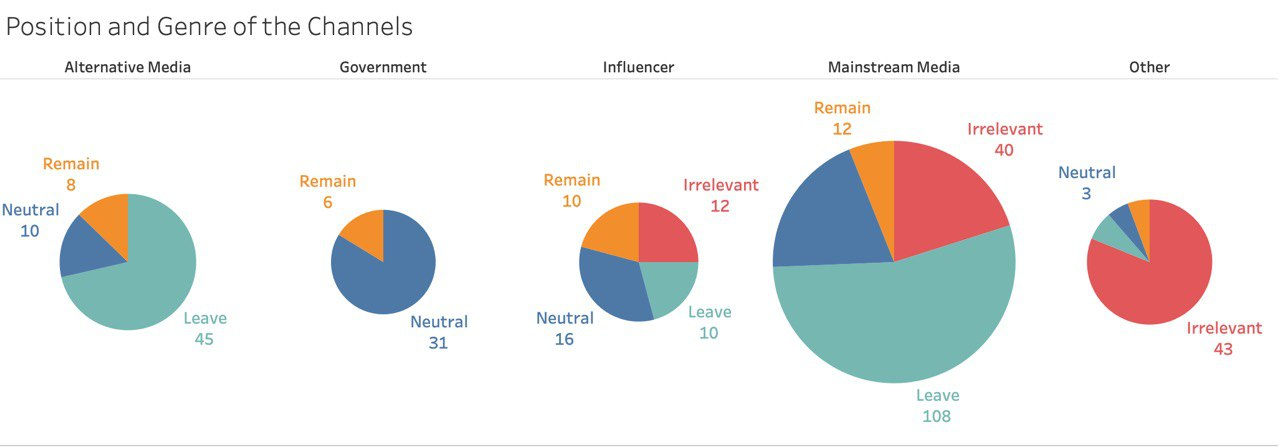

Second, in order to get a sense of the actual impact of polarization on YouTube in relation to Brexit, we extracted all the titles of the recommended videos per news source, i.e. The Mirror, The Telegraph, The Guardian and The Sun. Video titles are an important factor in getting a video recommended to users and nudging them into clicking and watching the content. Comparing video titles the refore says something about how these news sources, in relation to the algorithm, address audience concerns. Figure 8 highlights the association of words in the recommended video titles in relation to the various outlets.

Figure 7: Categorization of Recommended Channels

Figure 7 highlights that, contrary to earlier research on YouTube, where audiences are argued to be led to more fringe or niche content, we found that, when departing from mainstream outlets, users would be recommended more mainstream channels albeit mostly the same mainstream channels. There were some influencers, but these were not specifically ‘alternative political influencers’ that exploit the political potential of the platform to circumvent mainstream narrative reported by traditional news outlets, as has been argued by Rebecca Lewis. Moreover, ‘alternative media’ in our analysis refers to natively digital content (Rogers 5), i.e. outlets that were ‘born on the web’ rather than, as the outlets with which we began, migrated to the web. While Figure 7 does not distinguish unique channels, it does show that in general pro-Brexit positioning allows for more recommendations on YouTube. Finally, we also found some that we re ‘irrelevant’, i.e. channels without distinct political stance or content.

Second, in order to get a sense of the actual impact of polarization on YouTube in relation to Brexit, we extracted all the titles of the recommended videos per news source, i.e. The Mirror, The Telegraph, The Guardian and The Sun. Video titles are an important factor in getting a video recommended to users and nudging them into clicking and watching the content. Comparing video titles the refore says something about how these news sources, in relation to the algorithm, address audience concerns. Figure 8 highlights the association of words in the recommended video titles in relation to the various outlets.

Figure 8: Network of Common Keywords by Publication

Figure 8 shows that audiences of The Guardian will be recommended more ‘explanatory’ videos and ‘documentaries’. The Sun audiences get recommendations mostly of Nigel Farage addressing members of the European Parliament and, considering the timing of our research, the controversy surrounding the Duke and Duchess of Sussex Meghan and Harry. Counter to the findings of video and channel recommendations, where The Guardian and The Mirror shared more in common, the difference in non-shared videos reveals that audiences actually get different topics recommended. Videos recommended to The Mirror’s audience address Labour Party Leader Jeremy Corbyn as well as more specific videos about farms and dairy. The centrality of The Telegraph shows that audiences get recommended videos of topics that all other channels also touch on.

Figure 8: Network of Common Keywords by Publication

Figure 8 shows that audiences of The Guardian will be recommended more ‘explanatory’ videos and ‘documentaries’. The Sun audiences get recommendations mostly of Nigel Farage addressing members of the European Parliament and, considering the timing of our research, the controversy surrounding the Duke and Duchess of Sussex Meghan and Harry. Counter to the findings of video and channel recommendations, where The Guardian and The Mirror shared more in common, the difference in non-shared videos reveals that audiences actually get different topics recommended. Videos recommended to The Mirror’s audience address Labour Party Leader Jeremy Corbyn as well as more specific videos about farms and dairy. The centrality of The Telegraph shows that audiences get recommended videos of topics that all other channels also touch on.

5. Discussion

The experiments carried out by our group suggest that there is some evidence of progressive polarisation on Youtube, particularly around the already controversial subject of Brexit, although this is more prominent on the side of Leave users. The analyses of title recommendations also show that, in the frame of our smaller investigation, channels might share recommended videos, but that their individual recommendations largely broach distinctly different topics. T hus, the ‘content bubbles’ created by the recommender algorithm around Leave and Remain users rarely converge. Significantly, our findings also show that, despite clear evidence of slight polarisation around political issues, contrary to assumptions that frequently underpin claims about Youtube’s ‘radicalising’ effect, videos by mainstream media outlets were recommended with far greater regularity compared to those produced by native digital channels (such as alt-right influencers). What this suggests is that although the recommender algorithm seems to favour videos with clear partisan leanings, it does not inevitably lead users towards the most radical or inflammatory content.7. Conclusion

Previous research at the DMI Summer School has shown that personalization happens just when the users watch the entirety of the video. For this reason, we had to limit the videos chosen to five and also select videos that won’t be too long - we decided to have seven minutes as the maximum length. Clearly, further research which will take into account a more in-depth personalization i.e. watching more videos and longer videos would be beneficial in illustrating this phenomena. To avoid unnecessary laborious human-curated work, we would recommend the development and use of bots for this task. These could also help in generating a larger dataset compared to the relatively small one that we were able to create in the Winter School session. Crucially, youtube.tracking.exposed, as well as the other tracking.exposed tools are still under development. As with all projects, our experiments also held certain limitations that future research into the subject should acknowledge. Importantly, we did not look at the Youtube ‘home screen’ that offers users a separate collection of recommended videos when opening the webpage, and consider the effect the research personas created had on these recommendations - a strategy recommended by Arvind Narayan (Feuer). In addition, the sets of five videos chosen for both experiments, decided in partially in the interests of expediency as mentioned above, were not as uniform in age and tone as one might hope for optimal results. These pragmatic constraints had a slight detrimental effect for some of our results such as the Common Keywords graph, the relatively important amount of ‘irrelevant’ and ‘off-topic’ recommended videos obscuring some of the conclusions that could be drawn. A more precisely curated set of videos might thus have avoided some of these issues (which cropped up particularly strongly around the Mirror), and produced somewhat more refined datasets. Finally, taking up Rogers suggestions after presenting this report at the DMI Winterschool, we feel it can be beneficial to ‘confuse’ the algorithm by watching videos that would be ‘meant’ for opposing audiences in order to assess a ‘bias’ within the algorithm. In light of these conclusions, it is clear that the Youtube recommender algorithm certainly has subtle polarising effect on the content it proposes to users, yet this phenomenon is a more nuanced and complex one than is often claimed by straightforward accounts of Youtube radicalisation. Thus, future research aimed at appreciating this process in greater detail might focus particularly on some of the concerns that our project missed, such as the recommendations suggested by the ‘home screen’, and with the help of larger datasets produce more lucid and illuminating accounts of the impact of the recommender algorithm on Youtube user experience.7. References

Ledwich, Mark, and Anna Zaitsev. “Algorithmic Extremism: Examining YouTube 's Rabbit Hole of Radicalization.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.11211v1 (Submitted 24 December 2019). Lewis, Rebecca. “Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the Reactionary Right on YouTube.” Data Media Manipulation. Data & Society (2018). 1 November 2019. <https://datasociety.net/wpcontent/uploads/2018/09/DS_Alternative_Influence.pdf>. Munger, Kevin, and Joseph Phillips. "A Supply and Demand Framework for YouTube Politics." OSF (2019). 4 November 2019. <https://osf.io/73jys/>. Tufekci, Zeynep. “YouTube, the Great Radicalizer.” The New York Times. 10 March 2018. 1 November 2019. <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/10/opinion/sunday/youtube-politicsradical.html>. Ribeiro, Manoel Horta, et al. "Auditing radicalization pathways on YouTube." arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.08313 (2019). Rogers, Richard. Digital Methods. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2013. Feuer, William. “Critics Slam Study Claiming YouTube ’s Algorithm Doesn’t Lead to Radicalization.” CNBC. 30 December 2019. 20 Januari 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/12/30/critics-slam-youtube-study-showing-no-ties-to-radicalization.html. Newton, Casey. “How YouTube Perfected the Feed.” The Verge. 30 August 2017. 20 Januari 2020. https://www.theverge.com/2017/8/30/16222850/youtube-google-brain-algorithm-video-recommendation-personalized-feed. Matthew Smith. “How left or right-wing are the UK’s newspapers. YouGov. 7 March 2017 https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2017/03/07/how-left-or-right-wing-are-uks-newspapers8. Appendix

8.1 Adèle Haenel and pro/against #metoo polarization

| Title | Type | URL |

| French actress Adèle Haenel accuses filmmaker of 'sexual harassment' when a minor | Video of reference | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QFRPci2wK2Y |

| Article title | Type | Article URL |

| « Adèle Haenel parle d’elle mais surtout elle s’adresse à nous. En un mot, elle est politique » | Pro-feminist | https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2019/11/08/adele-haenel-parle-d-elle-mais-surtout-elle-s-adresse-a-nous-en-un-mot-elle-est-politique_6018416_3232.html |

| « Adèle Haenel devrait saisir la justice », lui conseille la ministre | Against-feminist | https://www.nouvelobs.com/societe/20191106.OBS20761/adele-haenel-devrait-saisir-la-justice-lui-conseille-la-ministre.html |

| Channel title | Type | Channel URL |

| Valek | Anti-feminist | https://www.youtube.com/user/Valeknoraje |

| Anti-feminism | Anti-feminist | https://www.youtube.com/user/AntiFeminisme/videos |

| Marinette- femmes et féminisme | Pro-feminist | https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcP3HpPMKiQHsj7qDzu3q6g/videos |

| Osez le féminisme | Pro-feminist | https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3lZNxZeElkWmsKNMuLHUZQ/videos |

| Number | Type | Channel | Video URL | Length |

| 1 | against | Valek | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4G7xD6s5dFA | 04:24 |

| 2 | against | Valek | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qX5RhQAwCuY | 08:05 |

| 3 | against | Valek | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eup58lgzPJc | 06:34 |

| 4 | against | Valek | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=usoMpgySmx0&t | 3:07 |

| 5 | against | Valek | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YGV6DBoGVV4 | 8:53 |

| 1 | pro | Osez | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jiFRlpSWv8I | 1:11 |

| 2 | pro | Osez | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qn_mz8UMjgA | 7:48 |

| 3 | pro | Osez | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uraCYlPaCWY | 7:24 |

| 4 | pro | Osez | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zxAhhgC6554 | 3:00 |

| 5 | pro | Osez | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=637NkjxDTGg | 5:00 |

| Title | Type | URL |

| London's Big Ben must 'bong for Brexit' on January 31, say MPs | Video of reference | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i7i6zUCXRO4 |

| Publisher | Round | Subscribers | Brexit position |

| The Guardian | 1 | 1.12M | Remain |

| The Mirror | 2 | 22.6K | Remain |

| The Telegraph | 2 | 822K | Leave |

| The Sun | 1 | 576K | Leave |

| # | Video Title | URL | Video ID | Publisher | Date | Views | |

| 1 | Boris Johnson confronted by medical student over 'PR stunt' | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q7edg_A4P4o | q7edg_A4P4o | The Mirror | 1/11/2019 | 694 | |

| 2 | Britain Talks: Vegan fashion blogger Sarah King meets third-generation dairy farmer Abi Reader | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=znCBjKTqXe4 | znCBjKTqXe4 | The Mirror | 30/6/2019 | 264 | |

| 3 | Jeremy Corbyn's social care pledge to the country | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X_Xm4K2Yh-0 | X_Xm4K2Yh-0 | The Mirror | 9/12/2019 | 347 | |

| 4 | Britain Talks: What happened when a Syrian refugee met a committed Brexiteer | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=klhr1T3cWKk | klhr1T3cWKk | The Mirror | 30/6/2019 | 293 | |

| 5 | Britain Talks: Brexit Remainer meets Leave voter to discuss EU referendum | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EfwOCLYK4ZQ | EfwOCLYK4ZQ | The Mirror | 17/04/2019 | 4694 | |

| 1 | EU referendum: lies, myths and half-truths | Guardian Explainers | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G5AbdJwBDag | G5AbdJwBDag | The Guardian | 15.6.2016 | 21.515 |

| 2 | Brexit result: 'Now we can look forward to a good Great Britain' | EU referendum | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mHroD4w2xxE |

mHroD4w2xxE | The Guardian | 24.6.2016 | 14.337 |

| 3 | EU referendum explained: Brexit for non-Brits | Guardian Animations | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7H9Z4sn8csA | 7H9Z4sn8csA | The Guardian | 31.5.2016 | 67.673 |

| 4 | The EU costs you the same as Netflix - is it worth it? Rem Koolhaas thinks so. | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1lsLXRV5ldI | 1lsLXRV5ldI | The Guardian | 21.5.2019 | 69.324 | |

| 5 | What is article 50? | Brexit and the EU referendum explained | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZkHtbVAcTbM | ZkHtbVAcTbM | The Guardian | 29.6.2016 | 28.206 |

| 1 | MPs pass Boris Johnson's Brexit Withdrawal Bill paving the way for Brexit in January | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GhiHk3FWjlU | GhiHk3FWjlU | The Telegraph | 20 dec. 2019 | 41.208 | |

| 2 | Five reasons to love Brexit | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y5Ikf1J47dg | Y5Ikf1J47dg | The Telegraph | 29 mrt. 2019 | 9.111 | |

| 3 | EU Referendum: Vote Leave's key claims about Brexit | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_K0fOMViz0 | c_K0fOMViz0 | The Telegraph | 3 jun. 2016 | 16.462 | |

| 4 | The EU's publicity stunts on British prime ministers over Brexit | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ANgJT5Ra_s | 6ANgJT5Ra_s | The Telegraph | 17 sept. 2019 | 171 504 | |

| 5 | EU Referendum: Who's more likely to vote for Brexit? | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lM6byZyTwto | lM6byZyTwto | The Telegraph | 26 feb. 2016 | 8.541 | |

| 1 | Could a No Deal Brexit be the beginning of the end for the UK? | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-p_96YAHZz4 | -p_96YAHZz4 | The Sun | 2 aug. 2019 | 79.738 | |

| 2 | Britain on way to Brexit as MPs FINALLY back Boris Johnson’s deal to leave in 42 days | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y11uWHIE18s | Y11uWHIE18s | The Sun | 20 dec. 2019 | 115.434 | |

| 3 | Boris Johnson to unveil final masterplan for Brexit deal | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yh4lUi-5ccA | yh4lUi-5ccA | The Sun | 1 okt. 2019 | 147.381 | |

| 4 | MEPs battle after Commons reject Brexit deal | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0JaK3hbfm4 | v0JaK3hbfm4 | The Sun | 13 mrt. 2019 | 373.477 | |

| 5 | MPs back Boris' deal but WRECK chances of Brexit on Oct 31 | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DwkWuR_9Fgs | DwkWuR_9Fgs | The Sun | 22 okt. 2019 | 56.996 |

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No 825974-ALEX, with Stefania Milan as Principal Investigator; https://algorithms.exposed).

| I | Attachment | Action | Size | Date | Who | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

image1.png | manage | 273 bytes | 14 Feb 2020 - 20:19 | SalvatoreRomano | |

| |

image17.png | manage | 240 K | 14 Feb 2020 - 20:43 | SalvatoreRomano |

Edit | Attach | Print version | History: r6 < r5 < r4 < r3 | Backlinks | View wiki text | Edit wiki text | More topic actions

Topic revision: r5 - 24 Feb 2020, SalvatoreRomano

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback