Do not forget to share this picture...the social lives of solidarity hashtags

Team Members

Marloes Geboers (Visual Methodologies, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences)Jelmer Kos (Journalism MA, University of Amsterdam)

Rick Plantinga (Journalism MA, University of Amsterdam)

Carlos d’Andréa (Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil)

Maja Sawicka (University of Warsaw)Shefali Bharati (New Media and Digital Culture, University of Amsterdam)

Sandra Dupuy (Communication for Development, Malmö University)

Constance Duncombe (The University of Queensland, Australia)

Serena Del Nero (DensityDesign, Politecnico di Milano)

Contents

Summary of Key Findings

When we are looking at the social lives of hashtags over time, we can see that hashtags that call out for action (#IranOutofSyria, #PrayforSyria and #resist) get resurrected whenever a disastrous event on the ground takes place (in our research this was the Khan Sheikhoun chemical attack in Syria of April 2017). Especially PrayforSyria took up when this tragedy took place, from being almost dead to being the largest of the three solidarity hashtags). From looking at the images that are tied to this particular hashtag we can see how symbolic, more generic, images (black ribbon, hearts and text based calls for solidarity images) are on the foreground at the peak of user activity, during and right after the attacks took place. We also analyzed the images that were tweeted in the days (12 days) after the attacks took place and see how two, much more specific and at times explicit categories of images take over: infant victims and images with a political message. Note, however, that the time span of 12 days is quite limited and it would be of great interest to research (re)tweeted images relating to this solidarity hashtag over a longer time span in the aftermath of this tragedy. Interesting visual categories we encountered were collages of children that depict a before and after situation (the children being alive and dead respectively). This is a genre that is quite different from what is known in humanitarian campaigning. Twitter being a platform following what's happening and thus playing a big role in the news sphere, one should also take into account research into the impact of news images, namely Barbie Zelizer's work (2010). Zelizer describes a visual strategy within journalism of depicting images of people 'about to die', to maximize public impact. However, what users do in user re-appropriations on Twitter is depicting two points in time: way before misery set in and the actual death itself. The children images, especially in the aftermath of the event, were picked up quite extensively and were thus being retweeted intensely (see tree map in the findings section). When we look at the emotions that are conveyed, we see how sadness and fear are structural emotions and during the event other emotions occur (love particularly). In the images a recurrent combination of emotions is conveyed and that is love and sadness (which is the second most correlated emotion found in the Facebook Reactions project of the summer school of 2017). An interesting question arises from this exploratory project: In 'flat' periods of user activity, how do people on the ground, in the place of actual suffering, use the solidarity hashtag to still attract attention for their cause? See image below, which was, sadly enough only tweeted or retweeted five times.. Figure 1: this image from the flat user acivity period before the spike was only (re)tweeted 5 times, despite the textual message, underpinning the urgency of the matter.

Figure 1: this image from the flat user acivity period before the spike was only (re)tweeted 5 times, despite the textual message, underpinning the urgency of the matter. 1. Introduction

As a way of following up on emotion research into Facebook (https://wiki.digitalmethods.net/Dmi/EmotionalClicktivismTheSequel) which was undertaken in a DMI summer school of 2017, this project engages into exploring ways of doing (visual) emotion research on Twitter. By using and following hashtags and their connecting tweet content relating to the Syrian conflict, we explored the visual language of emotionally laden hashtags in the Twitter space and their user re-contextualizations. This way we gain insight in how different tag communities use image content to convey emotional expressions. In Affective Publics (2015), Zizi Papacharissi, sets out a theoretical model for understanding affective publics: public formations that are textually rendered into being through emotive expressions that spread virally through networked crowds. Affective publics are defined as networked public formations that are mobilized and connected or disconnected through expressions of sentiment. Papacharissi’s research focuses on Twitter text, but communication these days on social media is increasingly undertaken through images. Just as using social buttons such as Facebook Reactions and the heart shaped Like button in Instagram, the way users produce, recontextualize and distribute images to engage with societal issues is part of contemporary connective action (Bennett & Segerberg, 2012). Recontextualizing images themselves by modifying the visual content and/or recontextualizing visuals through the use of text is a modality of user engagement that cannot be ignored. This project focusses on the user recontextualizations of image material that is connected to three hashtags in the Twitter space: #PrayforSyria, #IranoutofSyria and #resist. The selection of these hashtags and the study of their user recontextualizations are elaborated upon in the sections below.2. Initial Data Sets

We started off with one of the largest TCAT datasets available in DMI's servers: the bin with the keyword "Syria" with 133,566,442 collected tweets since November 23, 2011. This was subsetted to a time span surrounding the chemical attacks on Khan Sheikhoun in April 2017 (Feb 1 - Sep 1 2017) giving us 21.253.701 tweets. Based on a selection of three hashtags that were 'calling for action' (see selection procedure below) we ran three queries that gave us three datasets that could be used for the image-hashtag networks that show the visual language connected to these tags. In a following stage (qualitative) we narrowed down our analysis to the hashtag that significantly took up in the event time span (second time span, see below) and that was #PrayforSyria.3. Research Questions

What are the visual characteristics of images tied to hashtags concerning Syria?

Can we detect visual patterns connected to certain hashtags?

Do these images convey particular emotions?

What role do user re-appropriations play in the social sharing of emotions on Twitter?

Can we derive from ‘emotional images’ and their retweet data, shared attitudes towards the Syrian crisis in hashtag communities?4. Methodology

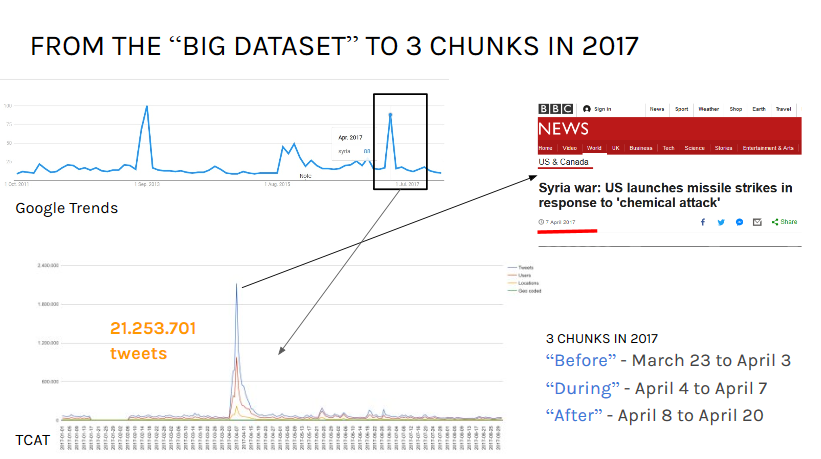

1) Working on the Syrian conflict with TCAT meant using the query bin named Syria, that's extracting tweets from 23 November 2011 giving us a mindboggling number of 133.334.433 tweets on January 8, 2018. We had to pinpoint a meaningful timeslot to narrow down the data and started off with a Google Trends overview to get a feeling of online user activity surrounding the Syrian conflict. When looking into the dynamics of calling attention for solidarity it is most interesting to look into a timeslot that provides for flat periods of user activity, spikes and depressions. This is all present in the period between March 23 2017 and April 20 2017. The TCAT timeline gives us similar user activities. See figure below. Figure 2

2) Based on a 21.253.701 tweets' subdataset collected between Feb 1 - Sep 1 2017, we identified on TCAT the "Top Hashtags" related to the keyword "Syria" during 3 periods of time:

Figure 2

2) Based on a 21.253.701 tweets' subdataset collected between Feb 1 - Sep 1 2017, we identified on TCAT the "Top Hashtags" related to the keyword "Syria" during 3 periods of time:Before the chemical attack - March 23 to April 3

“During” the chemical attack- April 4 to April 7

After the chemical attack - April 8 to April 20 We used the three time 'chunks' to obtain hashtag frequency through a spreadsheet. We built categories of hashtags that were related to a) Actors b) Places and c) Call for action. We analysed the 200 highest frequency of hashtags and categorised them under these headings. To us, call for action hashtags were the most relevant as they entailed an emotional character. The most frequent and common to all chunks were hashtags ‘PrayForSyria’, ‘resist’, and ‘IranOutOfSyria’. We then decided to go with the hashtag ‘PrayForSyria’ as a popular tag (17,294), common in all time frames and the most frequently used hashtag "during" the chemical attack, i.e. between April 4 and April 7.

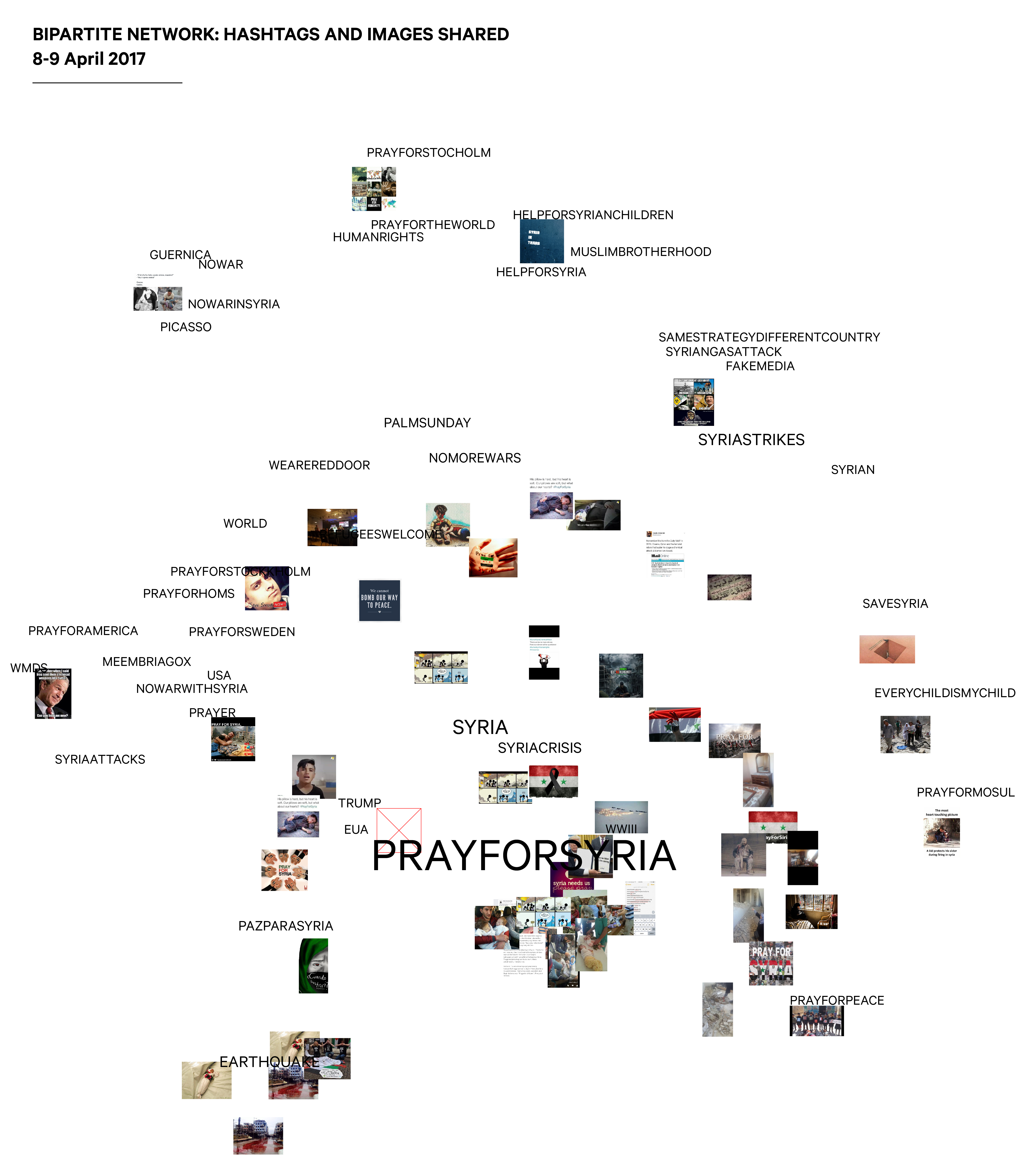

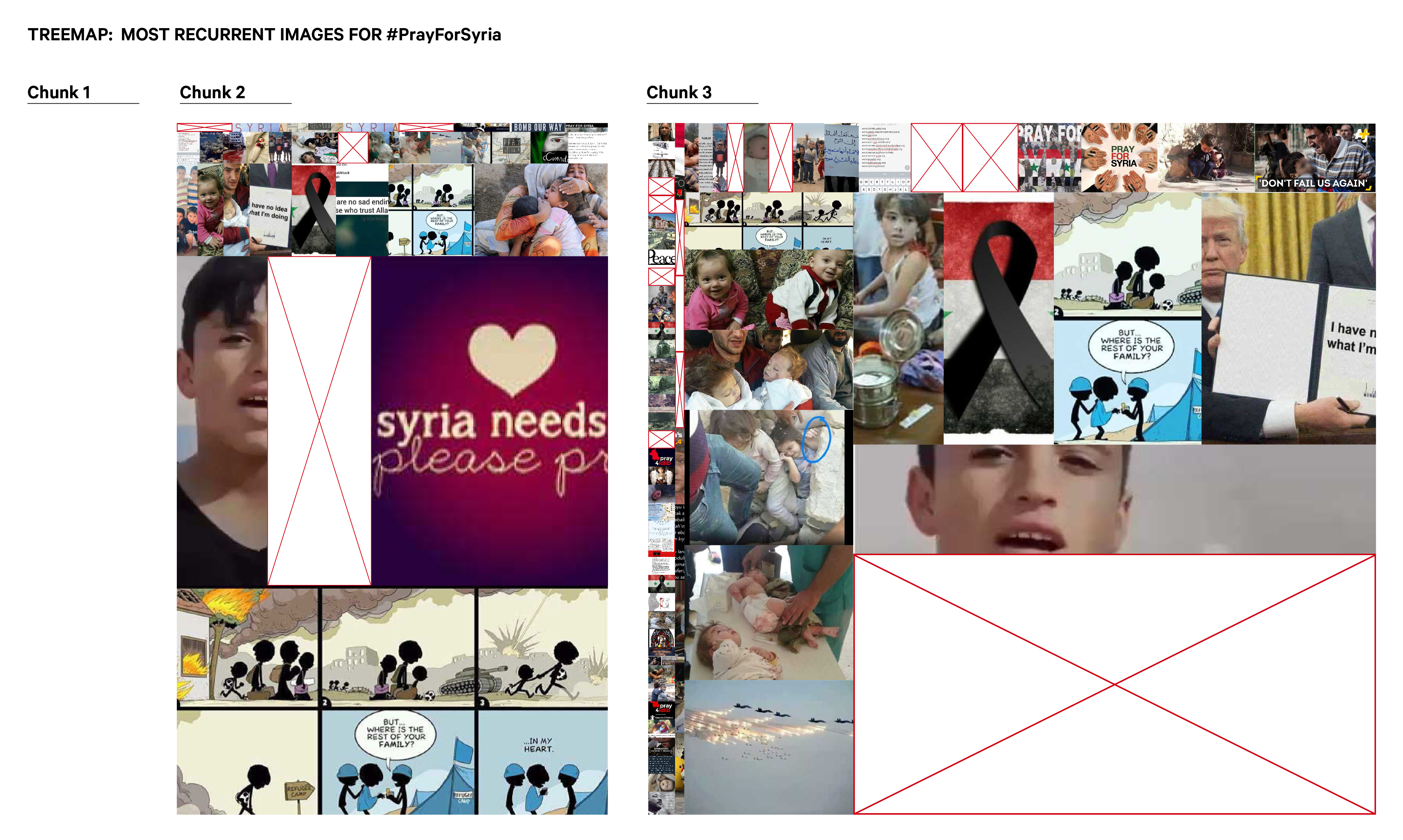

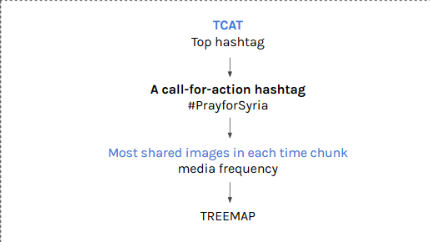

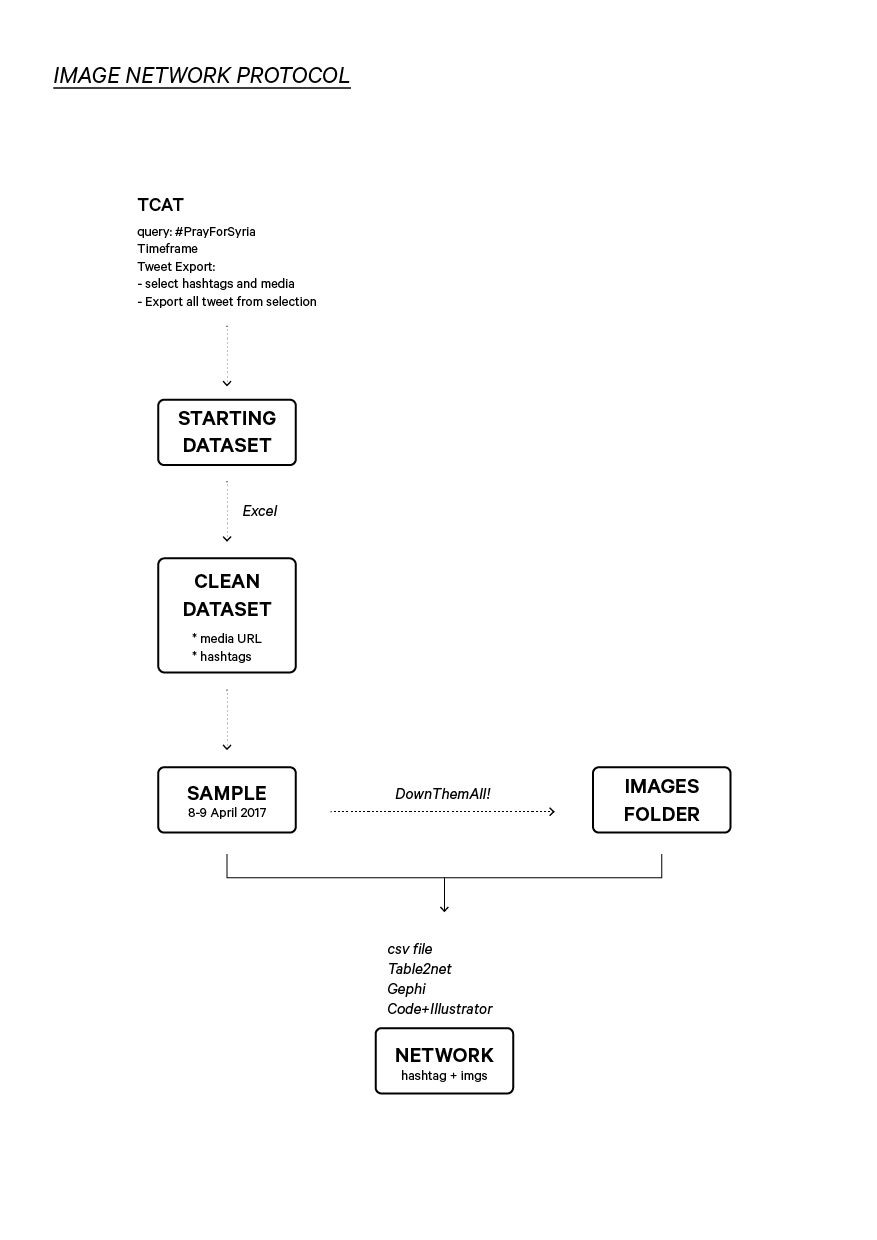

3) Our next step was to seek the images that accompanied tweets with the selected hashtag. For this, we used the media frequency feature of the TCAT and obtained the most shared images for each tweet from every time chunk. We could make two visualizations based on the data obtained: A tree map by Raw Graphs for the specific hashtag ‘PrayForSyria’ indicated the frequency of the use of the image in each time chunk (figure 3). And a bipartite network for dates 8-9th April tells which hashtags were shared and the images associated with these tags (figure 4). These dates were chosen as they lie in the third chunk, which was the longest time frame. Note, due to the restriction of time, it was only possible to come up with a image-hashtag network for a small time frame.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 4 Note a: blank images, were deleted by Twitter.

Note b: "chunk 1" seems empty - this is due to the fact that dimensions of the pictures reflect the frequency of thier occurance. In the case of chunk 1 there were only few pictures which were scarcely retweeted.

The protocols below summarize the methodological procedures:

Figure 5

Figure 5

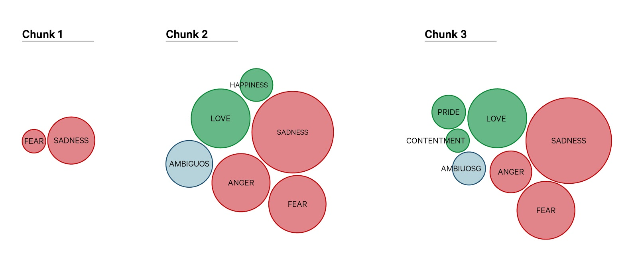

Figure 6 Step 4: To identify the emotional content of images, the project's team classified feelings associated with the most popular images (figure 7). The adopted classification of emotion was based on work by Laros and Steenkamp (2015) who identified the following eight basic emotions: anger, fear, sadness, shame, contentment, happiness, love and pride. To label images with emotions, we qualitatively analyzed the top 20 images in each time chunk for their emotional message. The classification of every image was deliberated with the team and arrived upon, also by cross coding. This ensured uniformity and clarity in coding.

Figure 7

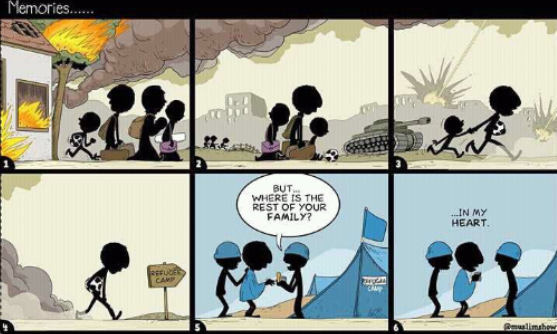

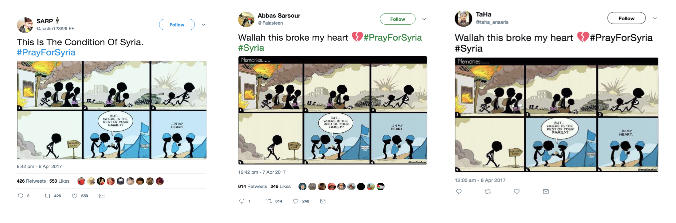

Figure 74) To study how tweets with images were retweeted, we decided to take a closer look at one image that evokes emotion and then queried the subdataset to identify the three tweets in which this image was embedded (Figures 8). This image was the most retweeted image in time chunk 3 and the third most retweeted image in time chunk 2 (the top image was not available, while the second was a screenshot of a video clip) Thanks to a new functionality implemented on TCAT by Emile den Tex, we could query the subdataset to identify the three tweets in which the image was embedded (figure 9) and trackback how two of them were retweeted over time (Video 1).

Figure 8

Figure 8

Figure 9

Retweet dynamics of the tweeted cartoon:

Video 1

Figure 9

Retweet dynamics of the tweeted cartoon:

Video 1

5. Findings

Visual media plays an important role in communicating narratives of conflict and war. The textual affordance of a hashtag also makes possible in procuring attention to the issue. In a study by Crilly, the author mentions that images of war posted on facebook construct a visuality focused on ‘the pain of others’ making the affected, injured, uprooted and killed by the conflict in Syria highly visible. (2017, p.133).The images discovered in our study do something similar. The hashtag “PrayForSyria” itself calls upon an emotion while the images tagged with this term range from the death of innocent babies to devastation of the peoples land. Over time analysis There are no images displayed in time chunk 1 in the treemap (figure 4) due to the phase consisting of only 6 images, 2 of which were not available. Chunk 2 and 3 have similar and overlapping images that are a mix of high-frequency images of victims, political slogans and sympathy. In the emotional content analysis of our images, we discovered that in the phase before the event, images display the suffering and war-torn land of Syria. They all convey sadness and fear for life. In the phase when the event takes place (chunk 2), the images soon become explicit. Infant victims feature majorly along with political messages. The emotion “anger” is introduced potentially as a response to America's interference with the missile launch. Happiness is another category comprising of life before violence. These include joyous playful children, living peacefully before the conflict claimed their lives. Pride is an interesting category in the aftermath phase. The images tied to this emotion call for faith in the almighty, brotherhood and spirit of the Syrian people. Love as an emotion overarches the event and the aftermath phase as a symbol of solidarity, sympathy and prayers. This is wholly missing from the dormant phase in time chunk 1. Combining the treemap (figure 4) and the emotion bubble visualization (figure 7), we can see how an interesting visual category is combining two emotions, love and sadness. They are conveyed through collages of children that depict a before and after situation (the children being alive and dead respectively). This is a genre that is quite different from what is known in humanitarian campaigning. Twitter being a platform following what's happening and thus playing a big role in the news sphere, one should also take into account research into the impact of news images, namely Barbie Zelizer's work (2010). Zelizer describes a visual strategy within journalism of depicting images of people 'about to die', to maximize public impact. However, what users do in user re-appropriations on Twitter is depicting two points in time: way before misery set in and the actual death itself. The children images, especially in the aftermath of the event, were picked up quite extensively and were thus being retweeted intensely (see tree map in the findings section). When we look at the emotions that are conveyed, we see how sadness and fear are structural emotions and during the event other emotions occur (love particularly). In the images a recurrent combination of emotions is conveyed and that is love and sadness (which is the second most correlated emotion found in the Facebook Reactions project of the summer school of 2017). Looking at the social lives of hashtags over time (figure 2), we can see that hashtags that call out for action (#IranOutofSyria, #PrayforSyria and #resist) get resurrected whenever a disastrous event on the ground takes place (in our research this was the Khan Sheikhoun chemical attack in Syria of April 2017). Especially PrayforSyria took up when this tragedy took place, from being almost dead to being the largest of the three solidarity hashtags). From looking at the images that are tied to this particular hashtag we can see how symbolic, more generic, images (black ribbon, hearts and text based calls for solidarity images) are on the foreground at the peak of user activity, during and right after the attacks took place. We also analyzed the images (figure 4) that were tweeted in the days (12 days) after the attacks took place and see how two, much more specific and at times explicit categories of images take over: infant victims and images with a political message. Note, however, that the time span of 12 days is quite limited and it would be of great interest to research (re)tweeted images relating to this solidarity hashtag over a longer time span in the aftermath of this tragedy. Retweet (user network) analysis Steiglitz and Dang-Xuan (2011) quote various studies that affective dimensions of messages (both positive and negative sentiment) on social networking sites, web blogs, discussion forums, etc trigger a more cognitive involvement of attention and higher levels of arousal, influencing, reciprocity, feedback, participation and social sharing behavior. (2011, p.218)This is exemplified in the accounts of users studied in our project, who added their own sentiment of sorrow and sympathy to the visual. This was then picked up by other users and spread exponentially through retweets. The accounts that posted the cartoon strip (figure 9) selected were picked up and retweeted differently as shown in the video. The account @Justin12393LEE has a total of 4838 followers and tweeted the image on 6th April, 2017 just before the event. On the day of the event itself, the same image was tweeted from the account of @iFalasteen with 59995 followers. This was picked up extensively and was retweeted more than 600 times. Interestingly, the day after the event, the image was posted again from the account of @taha_ansaris with 79 followers but was not retweeted. Social capital plays an important role in how twitter users discern value and create benefit for both the social network and themselves via three points that are, referrals, information access, and timing.(Steiglitz and Dang-Xuan, 2011. p.222).These points are imperative to fully comprehend user activity and behaviour regarding issues, attention and representation.

6. Discussion

There are several points of discussion and some limitations.As we have no arabic tags or key words in our query bin on TCAT, the date is most likely skewed towards the western perspective. It is of great interest to start a query bin that includes relevant Arabic hastags and keywords.

Also, in the user network analysis, on the surface level we see that the emotionally laden retweet (includes an emoji and more emotional language) might be retweeted more intensely, however from a close look into the user stats it is also possible that the less emotional frame was still shared more (retweet/follower ratio). This might suggest that users engage with less overt emotional framing more consistently; or it could indicate that the relative number of tweets in light of followers reflects a user's closer relationship with the individual who tweeted the image in the first instance. Further analysis would help to untangle these two issues.

Offline factors have the potential to influence the circulation of tweets and images relating to crises as well: news reporting of the chemical attack could have impacted on a user's awareness of the event and potentially their desire to tweet their support via #prayerforsyria. The response of political actors to the events could also have generated online discussion: for instance, the debate about the Trump administration's missile strike against Syrian air bases included discussion about Ivanka Trump's own tweets in response to the chemical attack. The symbiotic nature of Twitter and the news cycle is an important aspect of the circulation and resurrection of hashtags for solidarity that should be investigated further.

7. Conclusions

When we are looking at the social lives of hashtags over time, we can see that hashtags that call out for action (#IranOutofSyria, #PrayforSyria and #resist) get resurrected whenever a disastrous event on the ground takes place (in our research this was the Khan Sheikhoun chemical attack in Syria of April 2017). Especially PrayforSyria took up when this tragedy took place, from being almost dead to being the largest of the three solidarity hashtags). From looking at the images that are tied to this particular hashtag we can see how symbolic, more generic, images (black ribbon, hearts and text based calls for solidarity images) are on the foreground at the peak of user activity, during and right after the attacks took place. We also analyzed the images that were tweeted in the days (12 days) after the attacks took place and see how two, much more specific and at times explicit categories of images take over: infant victims and images with a political message. Note, however, that the time span of 12 days is quite limited and it would be of great interest to research (re)tweeted images relating to this solidarity hashtag over a longer time span in the aftermath of this tragedy. Interesting visual categories we encountered were collages of children that depict a before and after situation (the children being alive and dead respectively). This is a genre that is quite different from what is known in humanitarian campaigning. Twitter being a platform following what's happening and thus playing a big role in the news sphere, one should also take into account research into the impact of news images, namely Barbie Zelizer's work (2010). Zelizer describes a visual strategy within journalism of depicting images of people 'about to die', to maximize public impact. However, what users do in user re-appropriations on Twitter is depicting two points in time: way before misery set in and the actual death itself. The children images, especially in the aftermath of the event, were picked up quite extensively and were thus being retweeted intensely (see tree map). An interesting question arises from this exploratory project: In 'flat' periods of user activity, how do people on the ground, in the place of actual suffering, use the solidarity hashtag to still attract attention for their cause? See image below, which was, sadly enough only tweeted or retweeted six times.. Dominant emotions When we look at the emotions that are conveyed, we see how sad and fear are structural emotions and during the event other emotions occur (love particularly). In the images a recurrent combination of emotions is conveyed and that is love and sadness (which is the second most correlated emotion found in the Facebook Reactions project of the summer school of 2017). Also the role of hashtags in Twitter communication seems worth reconsidering. We regarded hashtags as a primary mode of framing of the visual content, especially of putting it in an emotional context. However, as we found out, the same visual content tagged with the same hashtag could be framed differently by the tweet text. This suggests that visual content should be coded and analyzed in reference both to the hashtags with which it is tagged, and actual text of the tweet in which it is embedded. Further research is needed into the ways in which emotions are conveyed by expressive means available for Twitter users: hashtags, text, and visuals.8. References

Bennett, W. Lance, and Alexandra Segerberg.(2012) “The Logic Of Connective Action.” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 739–768.,doi:10.1080/1369118x.2012.670661. Crilley, Rhys. (2017) . “Seeing Syria-The Visual Politics of the National Coalition of Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces on Facebook” Middle East Journal of Culture and

Communication 10 133–158.,doi: 10.1163/18739865-01002004 Laros, F.; Steenkamp, J. (2005). Emotions in consumer behavior: a hierarchical approach. In Journal of Business Research 58 (10), pp. 1437–1445. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.09.013. Papacharissi, Zizi.(2017). “Affective publics: sentiment, technology and politics.” Oxford University Press Stieglitz, Stefan & Dang-Xuan, Linh. (2013). “Emotions and Information Diffusion in Social Media—Sentiment of Microblogs and Sharing Behavior”, Journal of Management Information Systems, 29:4, 217-248 Zelizer, B. (2010). About to die, how news images move the public. Oxford University Press, Oxford PRESENTATION SLIDES JANUARY 12 2018 -- MarloesGeboers - 10 Jan 2018

| I | Attachment | Action | Size | Date | Who | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

180111_network-chunk3.jpg | manage | 3 MB | 15 Jan 2018 - 10:48 | CarlosDandrea | |

| |

180111_treemap.jpg | manage | 3 MB | 15 Jan 2018 - 10:47 | CarlosDandrea | |

| |

3 tweets cartoon.png | manage | 136 K | 15 Jan 2018 - 10:55 | CarlosDandrea | |

| |

cartoon.png | manage | 374 K | 15 Jan 2018 - 10:54 | CarlosDandrea | |

| |

emotional classification many images.png | manage | 59 K | 15 Jan 2018 - 10:52 | CarlosDandrea | |

| |

image network_protocol.png | manage | 27 K | 15 Jan 2018 - 10:39 | CarlosDandrea | |

| |

image_6ocurrencies_chunk1_prayforsyria_dontforgettoshare.jpg | manage | 27 K | 11 Jan 2018 - 12:48 | MarloesGeboers | |

| |

time.png | manage | 93 K | 23 Jan 2018 - 12:38 | MarloesGeboers | |

| |

treemaprotol.jpg | manage | 17 K | 15 Jan 2018 - 10:42 | CarlosDandrea | |

| |

video-dynamic-net-retweet.mp4 | manage | 1019 K | 15 Jan 2018 - 10:58 | CarlosDandrea |

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback