The People's Dashboard

The peoples dashboard is intended to be a critical layer on top of six different social media platforms: YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, LastFM, LinkedIn, and Instagram. For each of these platforms the following features are highlighted: navigation, platform, people and mix. In order to discover peoples data, an interface analysis was performed by collecting the language and all elements from the various platforms.Team Members

Erik Borra, Evelien Christiaanse, Caio Domingues, Yvette Ducaneaux, Inte Gloerich, Stefania Guerra, Alex Harrison, Hendrik Lehmann, Sabine Niederer, Gabriel Reis, Tommaso Renzini, Pavel Rodin, Jurij Smrke, Janina Sommerlad, and Esther WeltevredeIntroduction

In the digital age, people are likely to use and generate content on social platforms without being concerned about the structures and algorithms in the background of the online networks. Online content is increasingly metrified, processed, computationally and algorithmically aggregated and rearranged. As Mahnke and Uprichard argue, we are living an algorithmic turn in the whole world is strongly driven by computational algorithmic technology (Mahnke and Uprichard, 2014: 259). The social networks interfaces and dashboards show numbers, trends and feeds, with the purpose of empowering the user to have control over the content. However, the influence of the continuous automated processes is usually hidden and the information presented is often an assemblage of content produced by the users, by the platform and both. Considering the increasing importance of social media in peoples lives to find, foster and maintain meaningful connections to information, people, movements, and in all, the world at large (Langlois, 2014: 51), it is more and more necessary to develop a critical point of view over these platforms. During the DMI Winter School 2015, we aimed to identify human-driven data on six different social platforms: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Last.fm, YouTube and Linkedin. The purpose was to spot the peoples data and create awareness regarding the large automated content generated by the platforms. The analysis was conducted with the intent of creating a peoples interface per social media platform, what we called Peoples Dashboard. In parallel, an experiment also tried to understand how the networks balance human and platform content over time. By analysing the various elements of the existing interfaces, the Peoples Dashboard is a critique on social platforms towards a more transparent approach. It tries to reveal part of the internal engines and shows what is automated and what is peoples data (what has actually been contributed by oneself/friends/connections/followers). In other words, it tries to increase the understanding of what is actually social on social media nowadays.Research Questions

- How to create a dashboard that detects and renders visible peoples content and interaction in the highly mediated environments of social media platforms?

- By creating a peoples dashboard, which content is detectable as human-driven or machine-driven ?

Literature Review

In this research two topics had to be explored in order to create a plugin with the purpose of critically analyze social media platforms. The realization of this project involved focusing on the topics of dashboard/interface critique and social media platform critique. Problems regarding these topics are: finding the social in social media, transparency in the representation of data displayed on dashboards and the effect of algorithms manipulating human data. Questions that needed an answer or a point of view were: Where is the social in social media? and How can we identify data generated by people and distinguish them from data produced by algorithms by the platform?.1. Social Media Platform critique

In The Like economy: Social buttons and the data-intensive web Gerlitz and Helmond identify and follow the data flows that emerge from the Like button on Facebook, taking into account the politics of this specific platform (Gerlitz, Helmond 2013: 2). On the one hand the act of Liking can be seen as a social gesture and categorized as data produced by human, on the other hand: the metrics of the Like button are algorithmically constructed and changed every time the Like button is pressed, and can thus be seen as platform driven. To identify data produced by people is a daunting task: often the two are mixed, as shown in the example of the Like button. No data is by nature purely peoples data, and no platform is by nature purely algorithmic. As Astrid Mager advocates: [...] algorithms, like all other technologies, should not be understood as merely technical [...]. Rather, they should be seen as socially constructed entities mirroring and solidifying socio-political norms and values. (Mager 2014: 61). Every platform has its own unique technical infrastructure that affects how data is treated. However, in order to work towards a peoples dashboard and a plugin that creates a more transparent layer on the interface of social media platforms, we need some sort of consensus about what can be considered to be more peoples data than platform-driven data. Comments (without spam created by bots), in that sense, might be the purest form of content generated by people on a platform without interference of an algorithm that recommends, reorders or affects this act in some sort of way. Another way to distinguish between people-driven and platform-driven data is to make the distinction between content and numbers, between qualitative and quantitative data. Benjamin Grosser has made a plugin: Facebook Demetricator, a script that demetricates Facebook stripping it from all its numbers and values. As Grosser explains on his website: No longer is the focus on how many friends you have or on how much they like your status, but on who they are and what they said. Friend counts disappear. 16 people like this becomes people like this. Through changes like these, Demetricator invites Facebooks users to try the system without the numbers, to see how their experience is changed by their absence. With this work I aim to disrupt the prescribed sociality these metrics produce, enabling a network society that isnt dependent on quantification. (Benjamin Grosser 2012) Metrics describe or quantify a state, i.e., characteristic, or a process, i.e., a dynamic, trend, or evolution.(Kay, et al 2013: 3) To strip a platform from its metrics could be a way to make visible and set the focus on content instead of numbers. A social media platform without quantification could be the first step to find the peoples data. A second step in the process of identifying peoples data could be to change the concept of metrics and turn it into our favor. By removing the automation (the metrics that are based on user interactivity) we can move towards what can be considered to be peoples metrics instead of platform metrics. 2. Interface and Dashboard criticism Having investigated ways in how to distinguish peoples data from platform-driven data, our next concern is to think about how this plugin can actually function as a critical layer on top of social media platforms. How should we define this critical layer? And maybe more importantly, what makes this layer to carry the name: critical? An interface is a point where two systems, subjects, organizations, etc. meet and interact (Oxford Dictionaries 2014). "Usually, an interface is understood as a technological artefact optimized for seamless interaction and functionality.[...] It is a cultural form with which we understand, act, sense and create our world. In other words, it does not only mediate between man and computer, but also between culture and technological materiality (data, algorithms, and networks)," (Andersen, Christian, and Søren Pold 2014: 1). Social media platforms are interfaces that enable the user to socially interact, mainly through an arrangement of graphical features like images, buttons, text fields, links, etc. Interfaces are a layer on top of the script of the website like the skin from our body. An interface hides the exact workings of the mechanisms of a social media website, making it easier to interact with it without getting distracted. A characteristic of this graphical layer is that it displays data in a simplified way through graphical features mentioned earlier. On Facebook, the Like button is a very straightforward symbol that represents a social gesture of liking content, giving it a thumbs up. On the platform level the Like button represents a function that counts the amount of likes and changes it value with +1, every time the Like button is pressed. The Like button is thus a simplified way to represent the data in the interface. A consequence of simplifying data is that it makes the platform less transparent. In this project we are trying to realize the opposite: making the workings of the platform more transparent, highlighting and thereby distinguishing human-driven data from platform-driven data. By creating an array of critical layers from the social media platforms and making a collage , we are able to visually compare them. This collage of critical layers of social media platforms can also be thought of as a dashboard, or to be more precise: a Critical Social Media Dashboard. Dashboards are [...] In simplest terms, they are single screens that aggregate and display multiple flows of data. Dashboards are a way of relating to a world manifested through data, somewhere between glancing and monitoring, of selective interaction, of lean back governance, constantly in motion. (Bartlett, Tkacz 2015: 1) In this project the Critical Social Media dashboard is a static dashboard, it contains time-freezed snapshots from the different social media platforms. The plug-in however counters this shortcoming, as it can be turned off and on dynamically whenever the user wants.Methodology

1. How to create a Critical Social Media Dashboard?

To create a critical peoples interface or dashboard, we selected six different social media platforms: YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, LastFM, LinkedIn, and Instagram. For each of these platforms we marked each features as one of four categories: platform, people, mix, and navigation. In order to discover peoples data, we performed an interface analysis by collecting the language and all elements from the various platforms. By zooming into these sites, we started to divide peoples raw content, that is non-automated data from data which is influenced by algorithms. By examining each of these features, we aim to create a critical layer which users can see the platform-driven elements of the interface so that users know what is human and what is not. The platform drive data are those elements that are pushed by the platform, either algorithmically generated or promoted commercial content. Examples of this includes ads, promoted content, friend suggestions, content recommendations, trends. The peoples data are those elements that invite or reflect user contributions and interactions. Consider ones username, profile picture, posts, tweets, uploads, comments, like, favorite, share, invitations, and others. Without further re-ordering or re-ranking. The mixed elements are made up of peoples data and content that have been re-ordered, re-ranked, rearranged and recommended by the algorithms of the platform. The news feed, activity feed, sticky content, birthday notifications, group invitations, have all been considered as mixed content because of how they can be pushed to the top of the feed. Finally, the navigational elements are any which guide a user through the platform. This includes: home, search, settings buttons. Using these categories, we then took screenshots from multiple pages of each platform in order to analyze their humanness. In order to estimate the humanness of a page, we will count the number of elements present in each section to see how much humans may or may not dominate the page.2. Apply content to categories by colouring

2.1 Plugin

As a part of building this research we wanted to build a plug-in so that anyone interested in learning about the nature of the platform that they are using can do so. In order to create a Firefox and Chrome Plugin with Peoples Content Invitation Dashboard mock-up, we had to find all the HTML objects corresponding with the previously listed features of the page and extract their class and/or id. Based on that we wrote a CSS that overrides the native style of these elements. In this way we could colour-code the previously established distinctions on top of chosen platforms.

The peoples dashboard demonstrates how the selected platforms manage peoples content on their sites in a static way.The People's dashboard is implemented as a user script which can be installed in GreaseMonkey (Firefox) or TamperMonkey (Chrome). Currently only the People's Dashboard is only implemented for Facebook With the installation of the plugin, available on GitHub http://bit.ly/peoplesdashboard, the social media platform Facebook can be experienced as a real-time dashboard. The special feature let the interface of the personal Facebook page appear in colours, referring to the people, platform, mixed and navigational data identified on the site. The plugin has been programmed in order to empower people to critically engage with social media and detect which content is actually people-driven or not.

2.2. Platform population

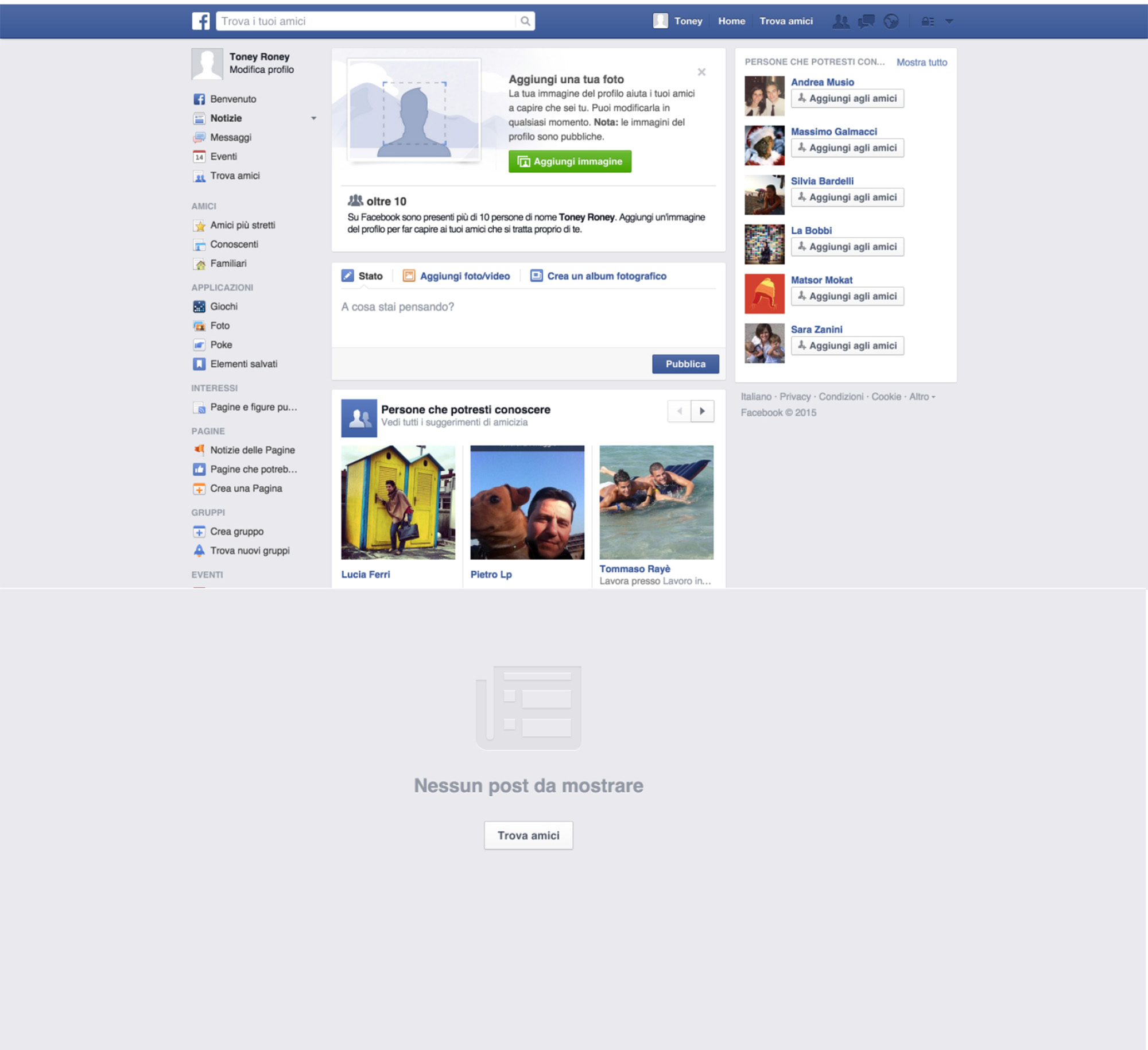

Finally, in what has been dubbed the Toney Roney Experiment , we wanted to create a new profile and observe how it becomes populated as a new user gets started. Where in the interface to people start appearing? This was done for three platforms:LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter. We started each platform with an empty profile. We aimed to have it as clean as possible, by signing up with newly made email addresses. Ideally, we would have used an incognito browser, however this meant that the screenshot plugin of choice would not work. Additionally, Facebook requires verification with a real phone number, in a possible attempt to keep out spammy or fake accounts. These two things meant that the platforms did have some basic information about Toney Roney.

In order to observe how the platform became populated, we measured the platforms at three stages, First with no friends/connections or followers , then with only one friend, connection, or follower, and finally with eight friends, connections or followers. The same categories were used to describe the features on each platform.

Algorithms are simple and enable multiple and constant reconfigurations of its elements, creating new possibilities which combine predefined with new data. As we begin to understand complex systems, we begin to understand that we are part of an ever changing, interlocking, non-linear, kaleidoscopic world. [...] the elements always stay the same, yet they are always rearranging themselves. So its like a kaleidoscope: The world is a matter of patterns that change [and have continuity], that partly repeat, but never quite repeat, that are always new and different, (Mahnke and Uprichard, 2014: 260). Zooming into the social media platforms, we investigated how much the kaleidoscopic dynamics of the algorithms influence the social within the platforms. Are we able to situate the different platforms in terms of peoples data; grey area and platform-driven data? How are the platforms ranked?

Findings and Discussion

The experiment with the empty research profile Toney Roney, which has been performed within the social media platforms LinkedIn, Twitter and Facebook, makes visible that each platform expands differently the more the platform becomes populated. Image 1: Facebook depopulated, potential friends with no add button.

Image 1: Facebook depopulated, potential friends with no add button.

The peoples dashboard

Apparently, the creation of a peoples dashboard, through analysing people-, platform- or mixed elements within the selected networking sites Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter, YouTube and LastFm, underlines the complex connection between platform and peoples content. The following (see image 3) shows the different platforms colored, referring to the influence of people (magenta), platform (cyan), mixed (dark blue) and navigational content (grey). The sites are in the correct order as listed in the previous paragraph. Regardless of the navigational data, the colored interfaces show the amount of platform versus peoples data which makes a ranking from less platform-driven content to more people-driven content possible. Our initial findings indicates that Instagram and YouTube are the most social and human-friendly platforms, whereas Facebook is more algorithm-oriented which makes it difficult for peoples data to exist or increase. The sites Twitter, LinkedIn and LastFm are positioned inside the grey and mixed area and therefore include many elements considered to be influenced by people as well as by the platform or put it differently, people's content that has been algorithmically rearranged. Image 3: The People's Dashboard, a guide to what is human and what is not on social media

Image 3: The People's Dashboard, a guide to what is human and what is not on social media

Conclusions

Although it is increasingly difficult to completely separate human and machine content, it is possible to recognize differences in the way each of the platforms deals with this subject. Some of them prioritize human content while others have a bigger algorithmic influence in the display of information and the process of populating the platform. As this research was only done in four days, there is still much to discuss. As they are now, the categories are problematic as it is nearly impossible to distinguish between the platform and the people. Features used by people, such as likes shares and comments inform the algorithms and rankings as presented by platforms. One can argue that all content on social media platforms has been algorithmically re-ordered since the algorithmically ordered website running on an algorithmically ordered browser, running on computers that already order algorithmically. This links to the assumption that the inspected elements for this study cannot easily be separated and defined either as people, platform or mixed data. As a matter of fact, there is a need for more precise terminology for the different stages of ordering the content. Accordingly, developing a vocabulary and qualifications for the kind and degree of user- and machine-action in these assemblages is crucial for further research Regardless, we find this to be a good start to researching the peoples data in social media. With time one could create more refined categories and analyse the pages better. Perhaps based on the amount of the page dominated by human features, rather than the number of human elements.Bibliography

Andersen, C. and Pold, S. Manifesto for a Post-Digital Interface Criticism. New Everyday. Media Commons, New York University (2014). Andersen, C.and Pold, S. Interface Criticism Aesthetics beyond the Buttons. Aarhus: Aarhus UP, (2011). Brügger, N. ; Finnemann, N. O. The Web and Digital Humanities: Theoretical and Methodological Concerns. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. (2013) Vol.57 (1), p.66-80. Gerlitz, C. and Helmond, A. The Like economy: Social buttons and the data-intensive web. New Media & Society (2013). Grosser, Benjamin. Facebook Demetricator Add On (2012) Langlois et al. Social media, or towards a political economy of psychic life in Unlike Us Reader. Institute of Network Cultures. Amsterdam (2014) Pages 50-60 Mahnke, M. and Uprichard, E. Algorithming the Algorithm in Society of the Query, Reader. Institute of Network Cultures. Amsterdam. (2014) Pages 256-270. Peters et al. Social Media Metrics - A Framework and Guidelines for Managing Social Media. Journal Of Interactive Marketing (2013) Vol.27 (4) pp.281-298.| I | Attachment | Action | Size | Date | Who | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Capture.JPG | manage | 9 K | 19 Jan 2015 - 10:57 | CaioDomingues | Legend |

| |

Copy_of_Linkedin_gentrification.gif | manage | 126 K | 19 Jan 2015 - 10:32 | CaioDomingues | Populating LinkedIn |

| |

Dashboard_comparison-01.jpg | manage | 77 K | 27 Jan 2015 - 09:43 | StefaniaGuerra | People's Dashboard Comparison |

| |

LinkedIn_shareanupdate.jpg | manage | 4 K | 19 Jan 2015 - 09:09 | CaioDomingues | LinkedIn share an update |

| |

feed_news_.jpg | manage | 349 K | 19 Jan 2015 - 10:22 | CaioDomingues | Depopulated Facebook News Feed |

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback