Public/Private Privacy Distinction in Iranian and American Google Play

A Comparative Study

Team Members

Team members: Arman Eslambolchi, James Sharp, Jack O'Carroll Part of the project: 'Apps and Their Practices: A comparative issue analysis across app stores and countries' Facilitated by Esther Weltevrede and Anne HelmondIntroduction

This paper is an attempt to report the findings of a brief comparative study on the representation and ordering of apps on the Google Play app store regarding privacy issues within two different languages and two different countries. In other words, the area of interest of this short research is comparing how we can detect changes and differences through the lens of a specific (and prominent) app store if we pick the same subject (privacy in this case) and analyze the results in each respective language. It should be noted, however, this study makes better sense if we consider it as a part of a more thorough project on ‘Apps and Their Practices’. This project contributes to empirically analyzing and conceptualizing the app space (cf. Dieter et al., 2019). It does so by comparing issues across app stores in various countries as well as attending to the infrastructural layers enabling app development for devices. Within media studies, apps are increasingly receiving attention as an object of study, and this project contributes to the empirical analysis and conceptualization of apps. Contrary to the web, which was originally imagined as a shared information space (Berners-Lee, 1996) and social media platforms, which were initially conceptualized as user-generated and/or spaces for social connectedness (Van Dijck, 2009; 2013), apps have been conceived as informational commodities from their inception (Daubs & Manzerolle, 2015; Morris & Elkins, 2015; Nieborg, 2015). This is related to the conceptualization and implementation of the app store as a primary place to discover, purchase and download apps. Today, mobile apps have become significant cultural and economic forms (Miller & Matviyenko, 2014). With the average user spending almost 1.5 months using apps per year, apps have become deeply embedded in our everyday lives. Apps are ‘mundane software’, not only because they support everyday practices, but because they embed themselves into our daily routines and habits (Morris & Elkins, 2015). In this project, we engage with the technicity of competing for ideas through apps in one of the most popular app stores, Google Play. How do Google Play stores modulate and regulate the visibility of certain kinds of apps? Which kinds of apps are ranked highly? How, where, and by whom is this visibility managed and controlled? These questions concern both algorithmic and economic power as well as their societal consequences. Perhaps in a so-called Post-API era, researchers could approach these questions by taking small steps toward the issue. That is where this brief project hopes to contribute.Research Relevancy and Questions

As mentioned above, this paper revolves around the notion of privacy and its presentation on Google Play while using different languages and trying to adjust the targeted country with the corresponding language. For this purpose, two countries have been chosen, Iran and the United States of America. These two countries, however, have not been chosen randomly. Iran has been selected because of the noteworthy current events in the country. During the last weeks of 2019, the country witnessed a huge wave of protests as the result of a sudden increase in the price of gasoline. The government’s response was brutal. But one of their responses was particularly notable for the purpose of this research. Iran’s government shut down the Internet across the entire country, and reportedly, used mobile tracking and mobile-spying malware to track down the protest organizers and activists (Kadivar, 2019). While activists and protesters have frequently had their privacy violated by the Iranian government, this recent internet blackout has rendered the existence - or nonexistence - of privacy protection applications an essential object of study and research. In light of this, we would like to see whether there is any noticeable differences with regard to how privacy protection applications are ordered and presented by Google Play for Iranian users querying in Farsi language compared with how privacy protection is presented through a more Western lens. In other words, how can we understand the notion of privacy through the lens of Google Play, while using different languages? And is the privacy protection application presented equally in different languages and countries on Google Play?Methodology

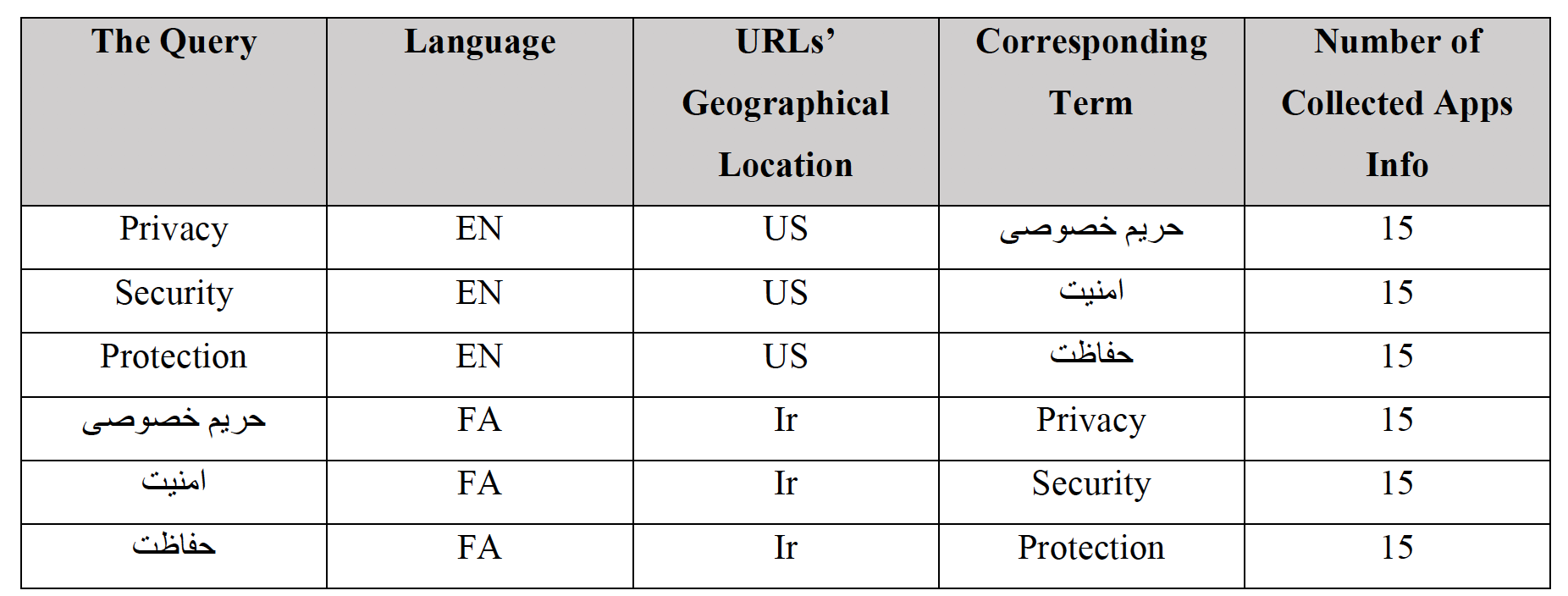

To answer the aforementioned questions some particular methods have been used. The data have been collected on the 16th of January 2020, querying the Google Play. The query design as it has shown in table 1, was carefully selected through some pilot study and trial and error process to find the best fitting query. For the Farsi queries, we consulted both a native language speaker and two Iranian professionals in the technology industry. Table 1 shows the final queries, both in English and Farsi, related to privacy issues that have been used for the reason for the data collection. Finally, three related queries have been selected. For the first step of the research, the English terms have been searched with the geographical location of the Google Play’s URL set to the US (https://play.google.com/store/search?q=vpn&c=apps&hlenfa&gl=us). Accordingly, Farsi terms have been queried with the URL of Google Play set to Iran (https://play.google.com/store/search?q=vpn&c=apps&hl=fa&gl=ir). Table 1 shows the final queries in both languages and the geographical location the term has been queried through Google Play.

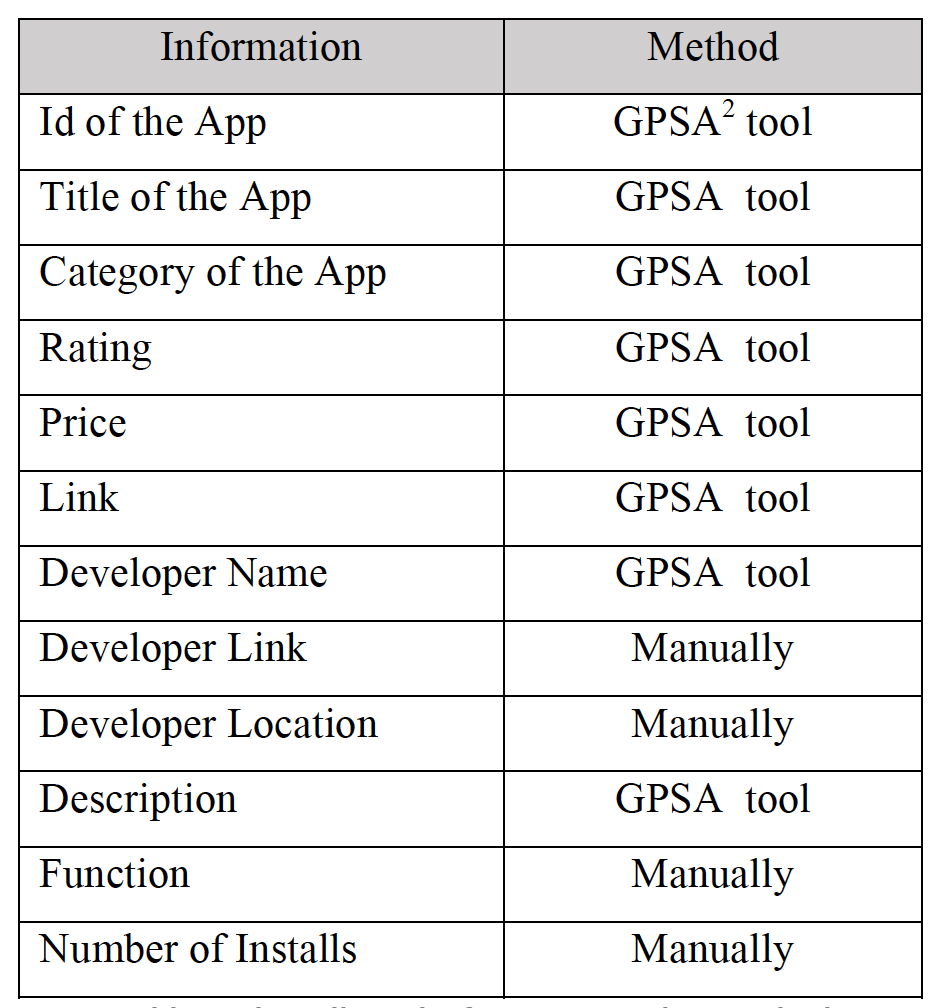

Table 1: query design for finding applications regarding privacy issues in two different languages and countries After designing the query and running it through the Google Play’s search section, the top fifteen applications were selected and categorized. Subsequently, the country of the apps’ developer together with the number of installs and ranking (according to the Google Play) were also collected. For this purpose, a combination of using the tool, Google Play Similar Apps, and adding information manually into Excel spreadsheets was deployed. Table 2 illustrates the information collected for each app (on top 15 apps for each query) for search query through the aforementioned methods.

Table 2: The collected information and its method

Finally, some visualizations have been concerning the information that has been collected. These visualizations have been created by the free version of the tool RAW Graphs and mostly with its Alluvial-diagrams tool. According to Raw Graphs website “Alluvial diagrams allow to represent flows and to see correlations between categorical dimensions, visually linking to the number of elements sharing the same categories” which is what this research hoped to detect. The next chapter of this paper demonstrates and describes some of the findings that this method made available.

Table 2: The collected information and its method

Finally, some visualizations have been concerning the information that has been collected. These visualizations have been created by the free version of the tool RAW Graphs and mostly with its Alluvial-diagrams tool. According to Raw Graphs website “Alluvial diagrams allow to represent flows and to see correlations between categorical dimensions, visually linking to the number of elements sharing the same categories” which is what this research hoped to detect. The next chapter of this paper demonstrates and describes some of the findings that this method made available.

Findings

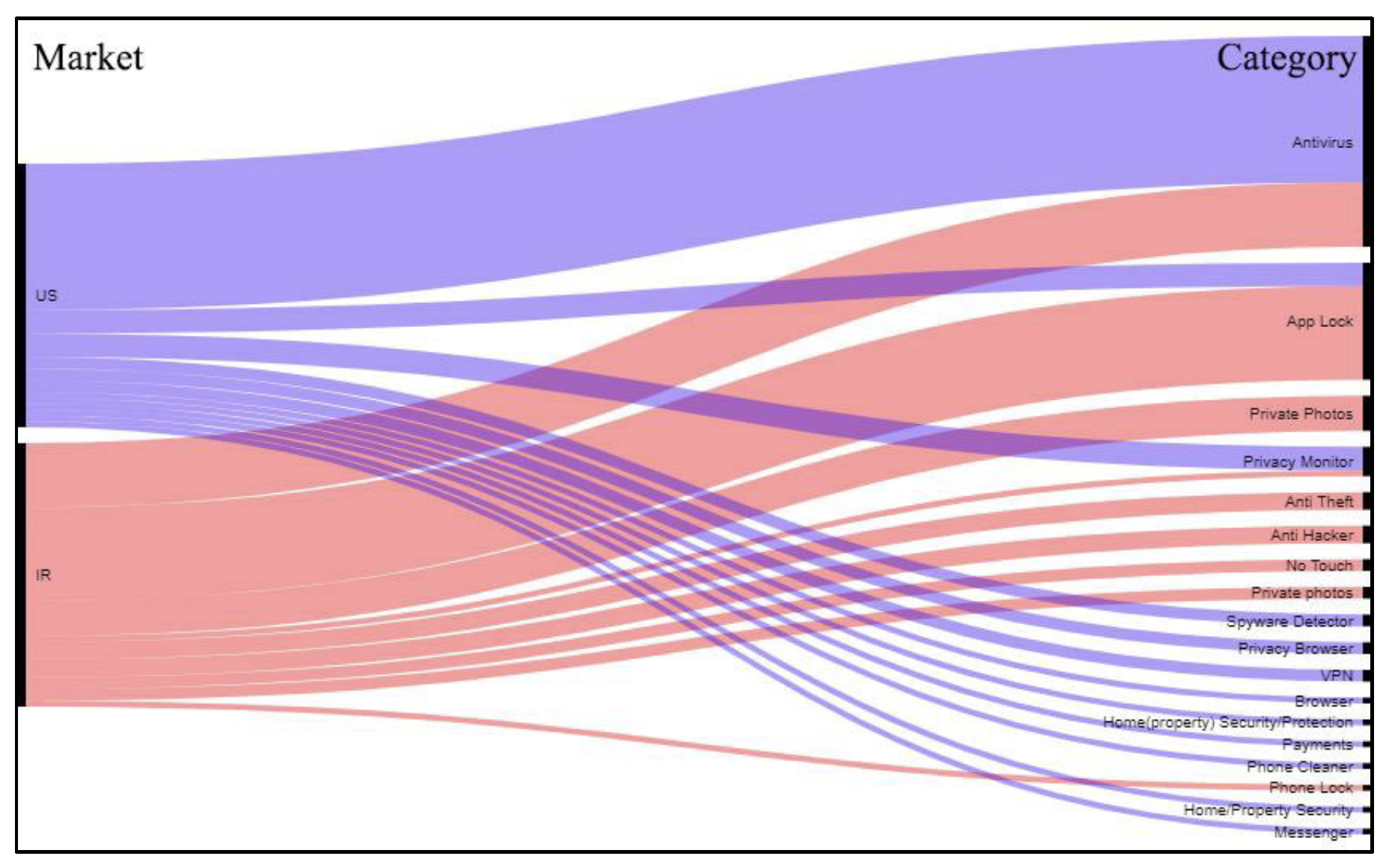

Contrary to the assumptions behind this research, the findings of this study show not only that the practices of apps regarding privacy issues differ among two countries but also that the very nature of apps which Google Play retrieve for the same query - but with different languages - are distinct. It is the first finding of this brief study. Figure 1 demonstrates one simple visualization that has been made by the aforementioned method and data. This visualization shows how the functionality of top presented applications among the two countries is different. Specifically, it shows how English queries for privacy-related applications with the geo-location of the US presents apps that are often well-known and reputable - usually anti-viruses or VPN’s - whereas for Iranian users ‘private privacy’ is more relevant as Google Play apps presented for the same query consist mainly of phone lock, anti-theft, and anti-hack software Figure 1: how not only the privacy apps’ affordances differ but their very nature is different among the two countries.

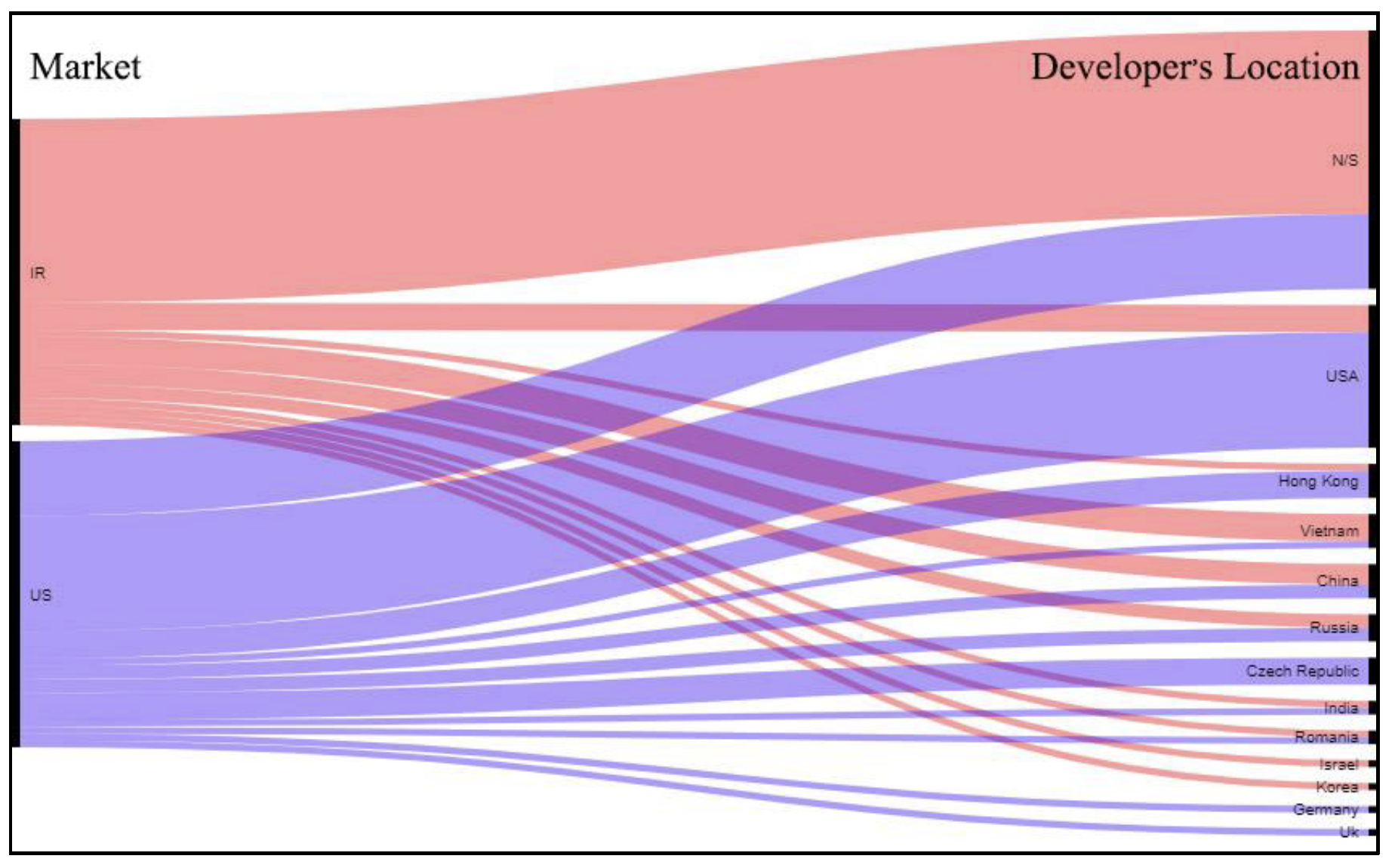

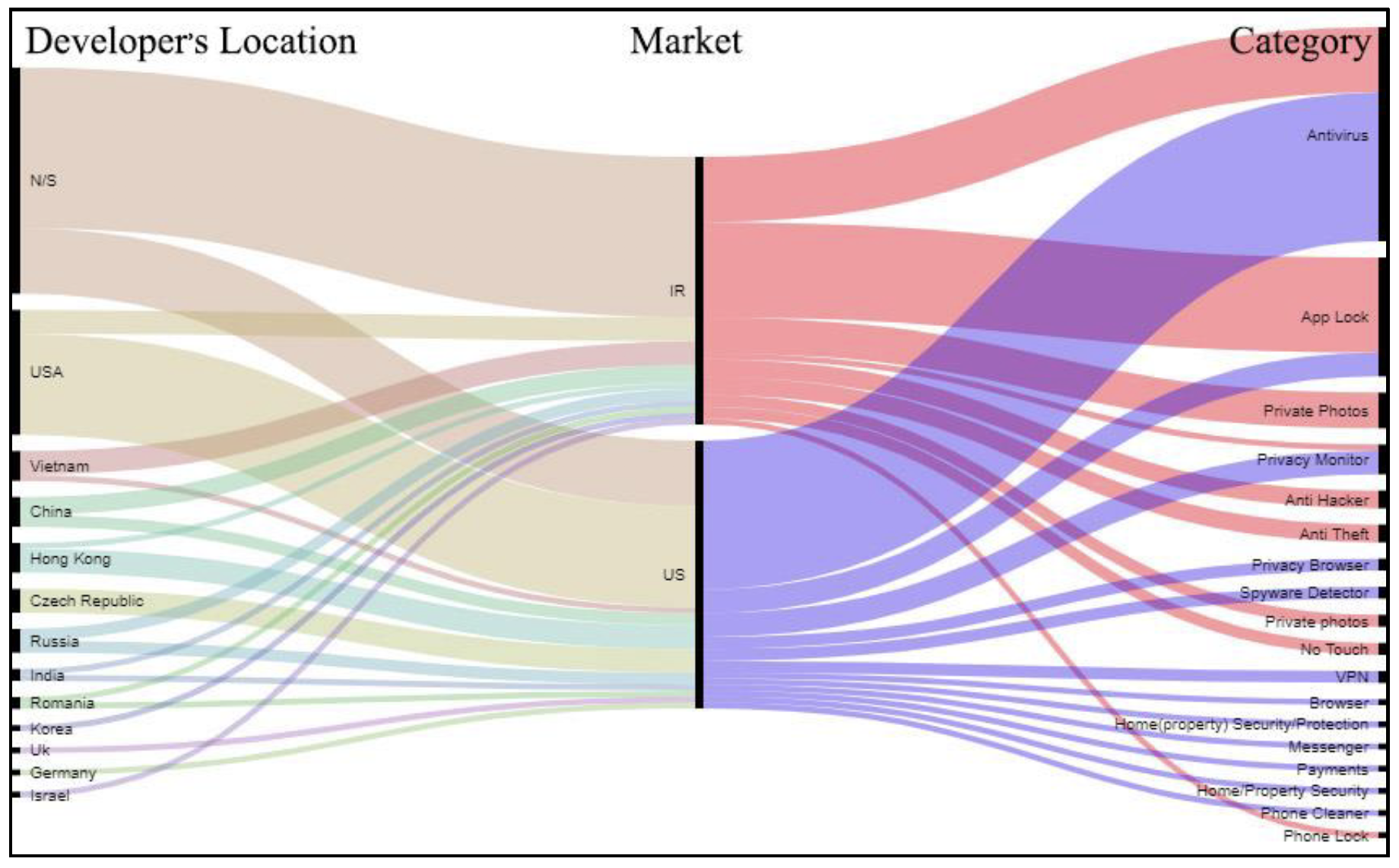

The second noteworthy finding of this brief research project revolves around the apps developers and their locations. According to this research data, privacy-related applications in the US market are mostly developed by American corporations and inside the United States. However, in the Iranian Market, most of the privacy applications have been developed in a not-specified location by a not-mentioned individual or group. The discussion section of this paper briefly mentions why this finding could be interesting and what potential arguments could follow from this. Figure 2 shows the visualization that made the second finding clear. It shows how app developers for the US market are mostly located inside the United States, and for the Iranian market, they are mostly from a not specified location. Moreover, some marginal countries could be detected as the app developers for both countries.

Figure 1: how not only the privacy apps’ affordances differ but their very nature is different among the two countries.

The second noteworthy finding of this brief research project revolves around the apps developers and their locations. According to this research data, privacy-related applications in the US market are mostly developed by American corporations and inside the United States. However, in the Iranian Market, most of the privacy applications have been developed in a not-specified location by a not-mentioned individual or group. The discussion section of this paper briefly mentions why this finding could be interesting and what potential arguments could follow from this. Figure 2 shows the visualization that made the second finding clear. It shows how app developers for the US market are mostly located inside the United States, and for the Iranian market, they are mostly from a not specified location. Moreover, some marginal countries could be detected as the app developers for both countries.

Figure 2: How app developers’ location differ between the Iranian and American market

The third and the final finding of this brief study reveals itself if we combine the first two findings. In other words, if we put the first two visualizations together and make a third one, as figure 3 tries to demonstrate, another noteworthy finding could be detected. It demonstrates that for the US market, most prominent privacy apps are those that have been made inside the country and other applications - presumably simpler to make -such as app- locks could be made in a not-specified country. By this finding, we might assume that these kinds of applications require less proficiency to make and therefore, they are not from a well-known developer, which makes the likelihood of not mentioning the country of developer higher. However, this is not the case for the Iranian market. As figure 3 demonstrates, even more complex privacy applications, such as Anti-viruses are from a not specified location. In this light, one could argue that privacy app makers would like to remain hidden if they target Iranian users.

Figure 2: How app developers’ location differ between the Iranian and American market

The third and the final finding of this brief study reveals itself if we combine the first two findings. In other words, if we put the first two visualizations together and make a third one, as figure 3 tries to demonstrate, another noteworthy finding could be detected. It demonstrates that for the US market, most prominent privacy apps are those that have been made inside the country and other applications - presumably simpler to make -such as app- locks could be made in a not-specified country. By this finding, we might assume that these kinds of applications require less proficiency to make and therefore, they are not from a well-known developer, which makes the likelihood of not mentioning the country of developer higher. However, this is not the case for the Iranian market. As figure 3 demonstrates, even more complex privacy applications, such as Anti-viruses are from a not specified location. In this light, one could argue that privacy app makers would like to remain hidden if they target Iranian users.

Figure 3: The combination of the first two findings reveals Iranian privacy developers would like to remain hidden

Figure 3: The combination of the first two findings reveals Iranian privacy developers would like to remain hidden

Discussion

The findings of this brief research confirm the differentiation of the conceptualization of privacy for different cultures. As Mizutani, Dorsey, and Moor in their article The internet and Japanese conception of privacy (2014) suggest, there is no universally accepted concept of privacy on the internet. They demonstrate that the notion of online privacy for Japanese people is completely different from the western concept of privacy: “Although Japan and other societies share at least a minimal sense of privacy, a base on which to build, robust privacy protection will not exist on the internet until an internationally accepted rich sense of privacy is developed” (P. 121). We are observing a similar distinction here, with regards to privacy protection apps between Iranian and American users. While the top privacy apps for American users are mostly for protecting their ‘public privacy’ (e.g. anti-viruses, private browsing, privacy monitor, etc), for Iranian users, top privacy apps practice is for protecting ‘private privacy’ (e.g. phone locks, file locks, anti-theft, etc.). In other words, Americans seem to be more concerned about protecting their property against external, organizational violation whereas Iranian users are mostly concerned about protecting their data from individual violations of privacy. The distinction between public and private privacy, as elucidated by Nissenbaum (2009), has many varieties. As Nissenbaum shows, for many people, privacy concerns are limited to concerns about control over personal information and protection from quite insular things such as the family, work-place and other personal environments. However, she forms the notion of ‘public privacy’ and argues that it is equally (if not more) important to protect data in the age of information, against institutional privacy violation. That is probably what we are observing in the findings of this research. One could argue that Americans, probably as a result of the higher digital literacy rate, are considering public privacy violations much more seriously than Iranian Google App users. On the other hand, it is difficult to gauge the extent to which our findings reflect the actual tastes (in terms of privacy) of Iranian and US customers, or whether our results instead point to a bigger, more geopolitical divide in terms of what privacy applications are allowed to be sold and consumed in Iran compared to the US. For example, it is indeed intuitively hard to know whether Americans are generally less concerned about their personal-privacy or whether public-privacy is merely prioritized over personal-privacy. Interestingly, an element of our research results which does not show up on any of the previous figures – is the complete lack of differentiation with regards to the ‘permissions’ of each app. We initially hypothesized that the Iranian app space might be more inclined to include apps that are more exploitative and willing to share private data. However, we actually found that any apps that came under the query term ‘privacy’ – whether searched in English or Farsi – were all almost identically exploitative in this manner. Apps, then, that ostensibly specialize in the protection of data and the promise of security – are all happy to display their intrusiveness in the ‘permissions’ section. This observation is placed here because it doesn’t illustrate a meaningful difference between the app markets but instead points to a more global and seemingly accepted problem of complicity on behalf of privacy applications in emboldening the very problem they are designed to limit.Limitations

It should be mentioned that this research, first of all, should be seen as a larger research project on Apps and Practices. Secondly, this brief research is better qualified as a kind of ‘pilot research’ to examine the functionality of this methodology. Therefore, the findings that this paper mentioned, as the result of this consideration which includes time and budget limitations, are far from being thorough or conclusive. The process of data collection should be more carefully conducted with more attention to the details of this process (such as what IP address on what time on which browser from what location is querying Google Play, and if this query is being influenced by past queries on the same browser/IP/ID/etc.). For the purpose of this research, these considerations have been intentionally omitted in order to save time and conduct this short ‘pilot research’. Further research could also bring in a third and possibly fourth country in order to compare the findings and also might test the Google Play search result with someone who is conducting the same query from the actual location. Besides, the amount of data for each query should be adjusted until the data saturation phase could be detected. Moreover, further research on the same topic could extend itself with some qualitative research method in order to offer a better, more comprehensive, comparison between the conceptualization of the notion of privacy between two distinct cultures. A cultural analysis could be an option to extend this research which is beyond the focus on the apps and their practices.Conclusions

Our conclusion ultimately hinges on the conception of app spaces as implicitly informing our day-to-day routines. Our research hopes to tentatively point to how the varying results between the Iranian app market, the US app market, query terms in English and query terms in Farsi can help us understand how app spaces have a meaningful effect on the reification of certain concepts in certain countries. In our case, it is clear that the version of ‘privacy’ presented to US customers who have entered English query terms contains a strong emphasis on public-privacy protection with companies such as McAfee and DuckDuckGo epitomizing this more corporate conception of privacy. In contrast, the conception of ‘privacy’ embedded into the daily routines of Iranian people – purely going by the app space presented by the Google Play store – is completely different. The aforementioned focus on ‘personal-privacy protection’ reveals an indisputable bias that would need to be penetrated with more qualitative research in order to fully understand its significance. At this juncture, it is difficult to know whether the app space accurately reflects a cultural difference in privacy that exists independently of the corporate app stores – or whether the Iranian app market is unfairly saturated with apps that don’t provide adequate security from – perhaps – more pressing privacy matters as viruses or other public-privacy concerns. On the other hand, our other main finding – the observation that apps presented via a Farsi query to Iranian consumers – arguably leads us into a territory that allows for a more tangible analysis. The fact that apps presented to US customers invariably contained information about the developers' country as well as – usually – an email address and formal point of contact, illustrates nicely how adjusted US consumers are to having their apps anchored in some kind of at least recognizable global technological system. However, Iranians, based on our research, have to rely upon apps for their privacy that are often totally unsourced and mysterious. Although the obvious takeaway here is that these apps are less hard to make and sell, which is interesting in of itself, our takeaway is that Iranian consumers have to accept a certain level of disorientation with regards to the products they are consuming. When this is viewed through the lens of how app spaces embed themselves into daily routines and thought patterns, we can uncover a notable difference in how notions such as reliability and traceability embed themselves differently in different countries. Overall, we are happy that our research has led us towards the discovery of subtle but meaningful differences in how app spaces are presented to consumers from different countries and how these varying presentations, in turn, embed themselves differently into the daily routines and thought patterns of these consumers. Unfortunately, the scale of our project does not extend to fully understanding the consequences of our results within the context of US sanctions on Iran or the specific role Google plays in presenting different conceptions of privacy when compared with other companies.Bibliography

Berners-Lee T (1996) WWW: past, present, and future. Computer 29(10): 69–77. DOI: 10.1109/2.539724. Dieter M, Gerlitz C, Helmond A, et al. (2019) Multi-Situated App Studies: Methods and Propositions. Social Media + Society 5(2): 1–15. DOI: 10.1177/2056305119846486. Daubs MS and Manzerolle VR (2015) App-centric mobile media and commoditization: Implications for the future of the open Web. Mobile Media & Communication. DOI: 10.1177/2050157915592657. Kadivar, M. (2019, November 27). Iran shut down the Internet to stop protests. But for how long? Retrieved January 27, 2020, from The Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/11/27/iran-shut-down-internet-stop-protests-how-long/ Miller PD and Matviyenko S (eds) (2014) The Imaginary App. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Mizutani, M., Dorsey, J., & Moor , J. H. (2014). The internet and Japanese conception of privacy. Ethics and Information Technology, 121-128. Morris JW and Elkins E (eds) (2015) There’s a History for That: Apps and Mundane Software as Commodity. The Fibreculture Journal (25): 63–88. DOI: 10.15307/fcj.25.181.2015. Nieborg DB (2015) Crushing Candy: The Free-to-Play Game in Its Connective Commodity Form. Social Media + Society 1(2). DOI: 10.1177/2056305115621932. Nissenbaum, H. (2009). Privacy in Context: Technology, Policy, and the Integrity of Social Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press. van Dijck J (2009) Users like you? Theorizing agency in user-generated content. Media, Culture & Society 31(1): 41–58. DOI: 10.1177/0163443708098245. Van Dijck J (2013) The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. New York: Oxford University Press.| I | Attachment | Action | Size | Date | Who | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Screenshot 2020-01-31 at 14.46.45.png | manage | 110 K | 31 Jan 2020 - 13:52 | AnneHelmond | Table 1: query design for finding applications regarding privacy issues in two different languages and countries |

| |

Screenshot 2020-01-31 at 14.47.55.png | manage | 101 K | 31 Jan 2020 - 13:53 | AnneHelmond | Table 2: The collected information and its method |

| |

Screenshot 2020-01-31 at 14.48.40.png | manage | 1 MB | 31 Jan 2020 - 13:54 | AnneHelmond | Figure 1: how not only the privacy apps’ affordances differ but their very nature is different among the two countries. |

| |

Screenshot 2020-01-31 at 14.49.15.png | manage | 1 MB | 31 Jan 2020 - 13:55 | AnneHelmond | Figure 3: The combination of the first two findings reveals Iranian privacy developers would like to remain hidden |

| |

Screenshot 2020-01-31 at 14.53.59.png | manage | 1 MB | 31 Jan 2020 - 13:55 | AnneHelmond | Figure 2: How app developers’ location differ between the Iranian and American market |

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback